Putting it all together

This chapter is adapted from the book Psychology Tools for Living Well. If you want to learn more about how cognitive behavioral therapists think about problems then this is a great place to start.

Looking at problems the CBT way

Not knowing why we feel the way we do can itself lead to feelings of helplessness and hopelessness. A classical medical approach to problems (including emotional ones) is to assess for symptoms, see if they match a recognised disorder and, if they do, prescribe the treatment for that problem. Having a name for what they are struggling with is enough for some people, but others want to understand more about why they are stuck.

One of the most helpful things about the CBT approach is the way that it breaks our problems down to make them understandable. This is great because:

- knowledge is power;

- understanding is half the battle;

- sometimes just knowing what is causing a problem can take the fear away.

If we can understand what is keeping a problem going then we are more able to do something about it. The way CBT works is a bit like a firefighter taking the time to understand what is fuelling a fire before deciding where to direct their efforts. Or a mechanic confronted with a misfiring car – her understanding of how cars work means that she pays attention to the engine rather than the wheels.

In this chapter we are going to learn some CBT ways of understanding problems.

How do we understand a problem with CBT?

Therapists who use CBT are trained to pay attention to problems in a certain way. If we want to understand how the CBT approach works we need to learn how to approach a problem.

Focus on specific events that happened recently

Therapists who use CBT often begin by paying attention to specific events that have happened relatively recently. This means that they attempt to identify problems like “Yesterday when I saw someone who looked like my attacker I was frozen to the spot with terror” rather than “I’m just always feeling so low that I’m not sure it’s worth it anymore”. Sometimes it takes a little practice to extract specifics from examples like the latter: when the therapist asked for some more details she was told “When I watched a programme last night on tv about friendships and realised I didn’t have anyone close anymore I felt so sad that I wondered what the point was in my existing”.

The reason that CBT focuses on specific events is because our lives are made up of specific moments all chained together. We live our lives moment by moment, and feel our feelings that way too. We might tell ourselves stories like “I had the most boring day ever” but chances are that your day was made up of some boring moments, and perhaps some mildly interesting ones too. If we want to pay attention to our thoughts and behaviours these happen moment-by-moment and we will miss important parts if we gloss over the details.

The reason that CBT focuses on things that are problems now is because problems that happened in the past may no longer bother you. Even if terrible things did happen in the past our suffering – what we want to relieve – happens in the present. One of the assumptions that CBT makes is that things happening in the here-and-now (perhaps thoughts, perhaps action) are contributing to that suffering. A final advantage of working on current material is that our memory for it is often better, which means that we can explore it in more detail.

Break moments down into helpful components

Once we have identified a specific and relatively recent event, the next job is to break it down into manageable parts. These might include:

- Triggers: What was happening just before the problem occurred?

- Situation: Who was there? What happened? When did this happen? Where did you experience the problem? (Who? What? When? Where?)

- Cognitions: What went through your mind at the time? (This might include thoughts, beliefs, interpretations, predictions, assumptions, memories, images, or a combination of these)

- Emotions: What did you feel? (Emotions can typically be described in one word: happy, sad, helpless, angry)

- Body sensations: What feelings did you notice in your body?

- Actions or responses: How did you respond? What did you do to cope? (This might include overt acts like standing up for yourself, or covert acts like distracting yourself in your mind)

- Context: We need to hold in mind the context in which an event is happening. For example, if David is having worries about his health then it is relevant and useful to know that he has suffered three bereavements in the past year.

Relationships and consequences

The next step is to look for relationships between the components. This is helpful for working out what happened and in what order. As a general rule:

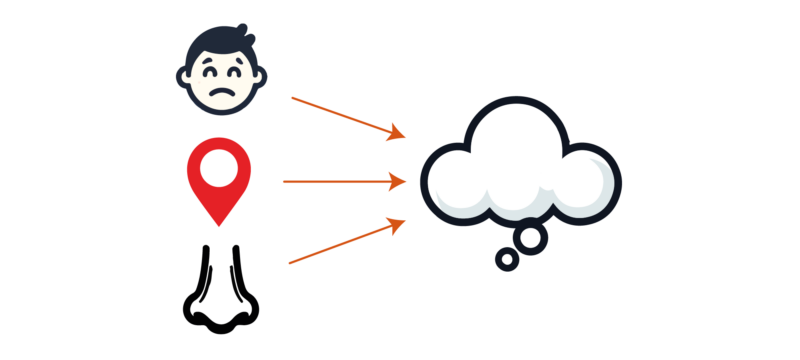

Anything we notice can trigger our thoughts

Common triggers for our thoughts include events, things around us (sights, sounds, smells), body sensations, other thoughts, or memories. We can also think about anything, so anything can be a trigger for our thoughts.

Figure 4.1: Anything we notice can trigger our thoughts.

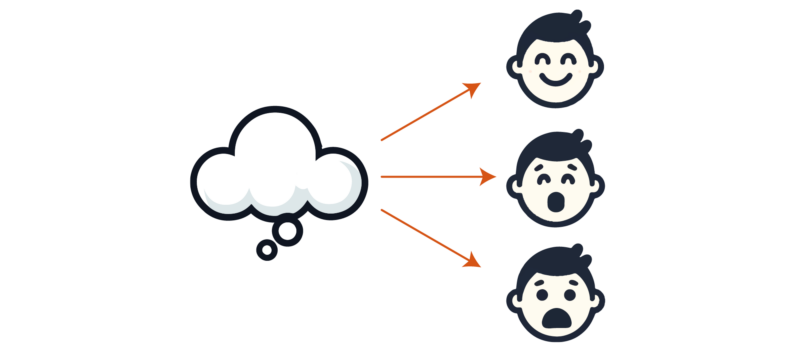

Thoughts lead to feelings

As we explored in the previous chapter, the way that we interpret situations affects how we feel about them. These interpretations can happen quickly and automatically. Remember, though, that our automatic thoughts are not always accurate.

Figure 4.2: Thoughts lead to feelings.

Actions lead to consequences

The physicist Isaac Newton’s third law of motion states that “Every action has an equal and opposite reaction”. Our actions are similar – everything that we do has a consequence. Some consequences are intended, but others are not.

A common step in CBT is to ask the question “What were the consequences of acting that way?”. You might have escaped a frightening situation with the (intended) consequence that you felt safer. But perhaps some unintended consequences were that you learned that it feels good to escape, and escaping became your ‘go to’ strategy for handling tricky situations.

Figure 4.3: Our actions have intended and unintended consequences.

Focus on what is keeping a problem going

A fire needs three things to start: heat, fuel, and oxygen. As long as those things are present the fire will keep on burning. We say that a fire’s maintaining factors are heat, fuel, and oxygen. With this knowledge, firefighters can choose which maintaining factor to target. Depending on the type of fire they are faced with they may decide to:

- remove the oxygen by spraying the fire with; CO2; or

- remove the fuel available to a forest fire by creating a ‘fire break’; or

- spray on water to remove heat.

CBT examines problems in a similar way: the focus is on maintaining factors. Like a fire it’s not so important to know what started it, but we do need to know what is keeping it going. Therapists who use CBT are trained to pay particular attention to any sequences that appear to get stuck in a loop or jammed (where an action feeds back to cause more of the problem).

Figure 4.4: CBT has a focus on what is keeping a problem stuck.

There are many different ways that human problems can be maintained. Some of the most common maintaining factors that can keep our problems stuck are illustrated below.

Figure 4.5: Common maintaining factors for psychological problems.

How problems persist

Psychologists have found that maintaining factors often join together in ‘typical’ ways to cause problems. In this section we will look at some common problems and explore the maintaining factors that keep them going.

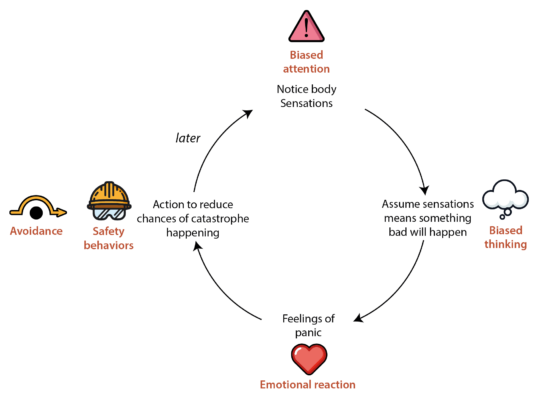

Anxiety

People who have panic attacks often notice ambiguous body sensations and assume that their presence means something terrible will happen. This way of thinking results in strong emotional reactions followed by understandable attempts to cope. The selective attention, biased thinking, and avoidance are important maintaining factors in panic. These are the areas that CBT treatment for panic will focus on.

Figure 4.6: The cycle of panic and the mechanisms that keep it going.

Depression

Similarly for depression, CBT researchers have found that people with low mood experience changes in thinking and behaviour and that these changes can keep the depression going. The diagram below shows how ‘depression mode’ can be maintained in some people.

Figure 4.7: One person’s cycle of depression with the mechanisms that keep it going.

Mixed problems

Many people struggle with more than one problem at once and not everyone’s problems fit neatly into models like those above. CBT is flexible though – using the same ‘building blocks’ it provides a framework for understanding problems so that and we can create our own models.

Figure 4.8: The building blocks of CBT can help us understand a huge variety of problems.

When Sally came to therapy she was really struggling. She and her therapist took the time to properly understand how she was feeling, and identify the things that were maintaining her distress. Using this new understanding Sally, her therapist, and her parents came up with a plan to help her feel better.

Making changes

Once we have an understanding of what is keeping a problem going we need to take action in order to get it ‘unstuck’. If we understand the maintaining factors we are in a good position to think of some solutions that are likely to help.

CBT is not just a ‘talking therapy’. Psychologists have found that to be really helpful a therapy has to help you to make changes in your life. It is better to think of CBT as a ‘doing therapy’.

The kinds of changes that CBT might help you to make will vary from person to problem. Some common strategies for change are:

Facing your fears

Marcus had been barked at by a large dog when he was five years old. Now, over a year later, his mum had brought him to see a psychologist because his fear of dogs was making it difficult for him to visit his grandparents who had two dogs. Marcus’ therapist helped him to overcome his fear by gently exposing him to dog-related triggers. They started by drawing pictures of dogs, then looking at photographs on the internet, playing with soft toys, and eventually meeting a gentle therapy dog. Marcus felt uncomfortable at times during this process, but with encouragement he was able to face his fears and overcome them. Six months later and he was best friends with his grandparents’ dogs.

Testing your assumptions

Ruby had been scared of escalators ever since she had been a child. She found it easy to imagine getting her clothing trapped, and getting seriously hurt. Her therapist encouraged her to make predictions about what would happen if she rode an escalator. Together they visited a local shopping centre and Ruby had a chance to test her assumptions. They began by watching other people ride the escalators and noting how many incidents occurred. Eventually Ruby felt safe enough to ride one herself, and was encouraged to experiment with by standing on different points of the step.

Thinking more accurately

Laura was very depressed when she started therapy. Her therapist encouraged her to record some of the thoughts she had when she felt at her worst. Laura’s thoughts were extremely self-critical: she pounced on flaws in herself that she would not even notice in someone else. When Laura realised that she spoke to herself in ways that she would never dream of speaking to another person she began to practice being less self-critical, and her therapist trained her to notice her achievements as well as her stumbles.

Replacing unhelpful habits

Phil had suffered from panic attacks for a long time and some years ago one of his doctors had prescribed him a strong anti-anxiety medication. Phil had not taken the medication for over a year, but still carried it everywhere with him ‘just in case’. He did everything he could to avoid the slightest symptoms of panic and when his therapist wondered aloud what would happen if he stopped carrying the medication with him Phil was initially reluctant. However, as therapy progressed Phil learned that he could deliberately bring on the symptoms of panic without experiencing any of the catastrophes that he had been worrying about. Phil replaced his unhelpful habit of avoidance with one of approach – and he found that he didn’t need the ‘crutch’ of the medication once sensations of panic didn’t feel so threatening.

Learning new skills

Joanne had always felt nervous when she was around other people and had a strategy of always putting their needs first because she assumed this would make her more likeable. During therapy Joanne learned some skills to become more assertive. Learning to assert herself gave her a new-found confidence. To her surprise she found that rather than rejecting her, people in her life seemed to respect her more.

We will explore the doing part of CBT more in later chapters. For the rest of this chapter we’re going to focus on understanding problems really well.

The CBT model in practice

For the rest of this chapter we’re going to look at three different techniques that CBT therapists use to understand problems. Once we have looked at some examples you will have a chance to try them yourself.

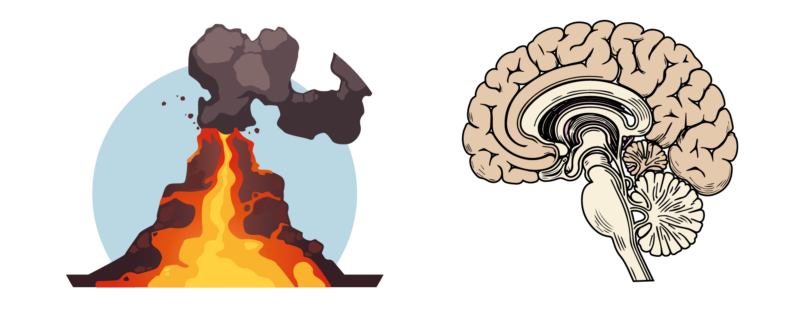

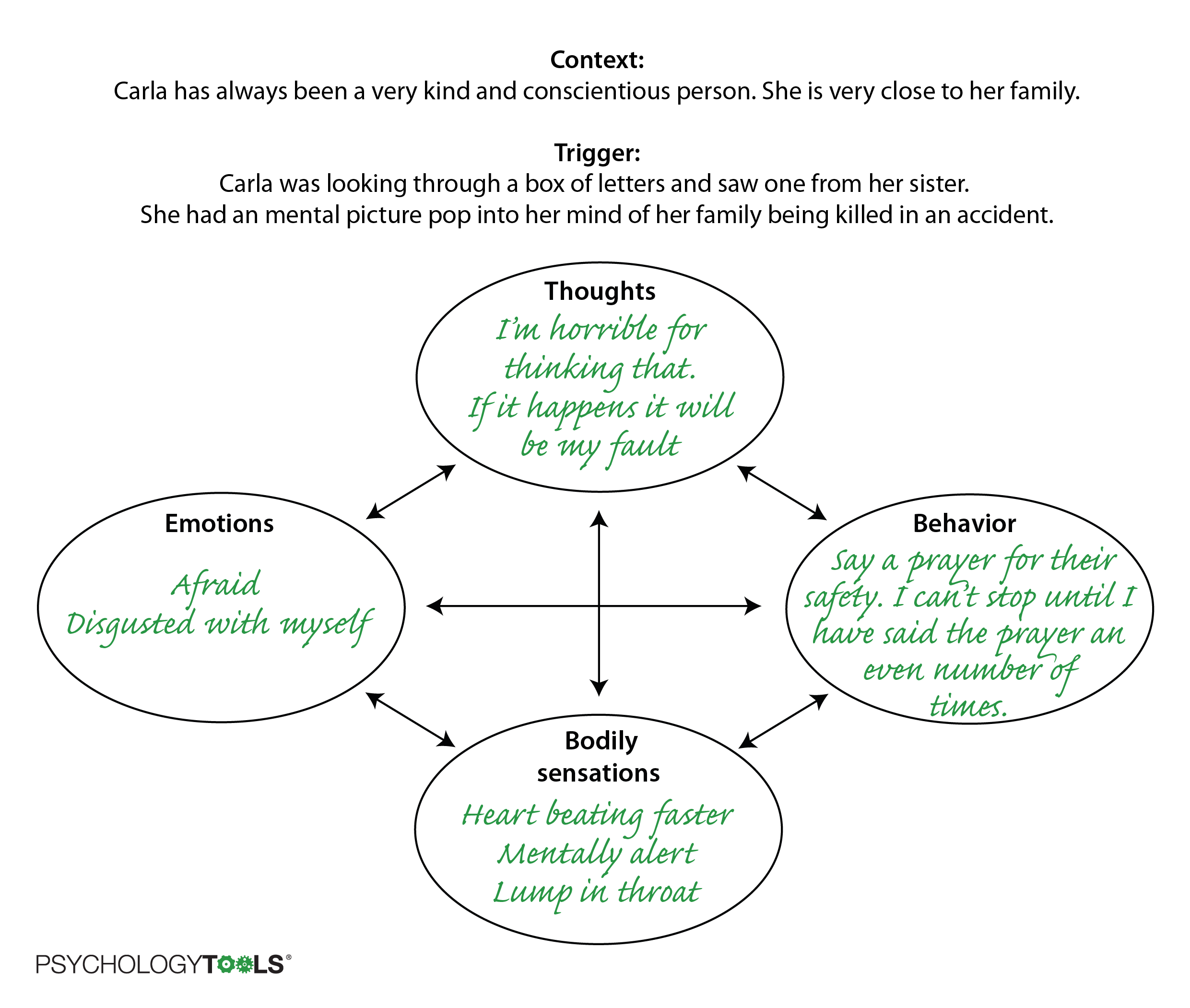

1. Cross-sectional model

Some things look complicated from the outside, but start to make sense when we see the inner workings. A good way of understanding complicated systems is to use a cross-sectional model. It’s called that because it’s like taking a snapshot (cross-section) of what is going on at one moment in time. We can use cross sections to understand how all sorts of things work, from volcanos to brains.

Figure 4.9: Cross sections help you to understand the inner workings of complex systems.

A CBT cross-section examines a situation for a short period of time and looks at some of the typical CBT elements: triggers, thoughts, feelings, and reactions. The CBT cross-sectional model is great for:

- understanding the connections between our thoughts, feelings, and behavior; and

- gathering data about problems as they occur so that we can look for patterns

Carla came to therapy because she was feeling very afraid most days. Her therapist explored some specific instances of fear with her, and drew elements of their conversation as a cross-section.

Figure 4.10: A cross-sectional model of one of Carla’s anxious moments.

Using the cross-sectional model helped Carla to notice some of the scary thoughts she had been having, and some of the ‘urges’ she experienced in response to them. When her therapist asked her to keep a record for a week she began to notice some patterns about when the thoughts appeared, and the kinds of predictions that her mind would make. This helped Carla and her therapist to make some plans about the treatment that would be most helpful for her.

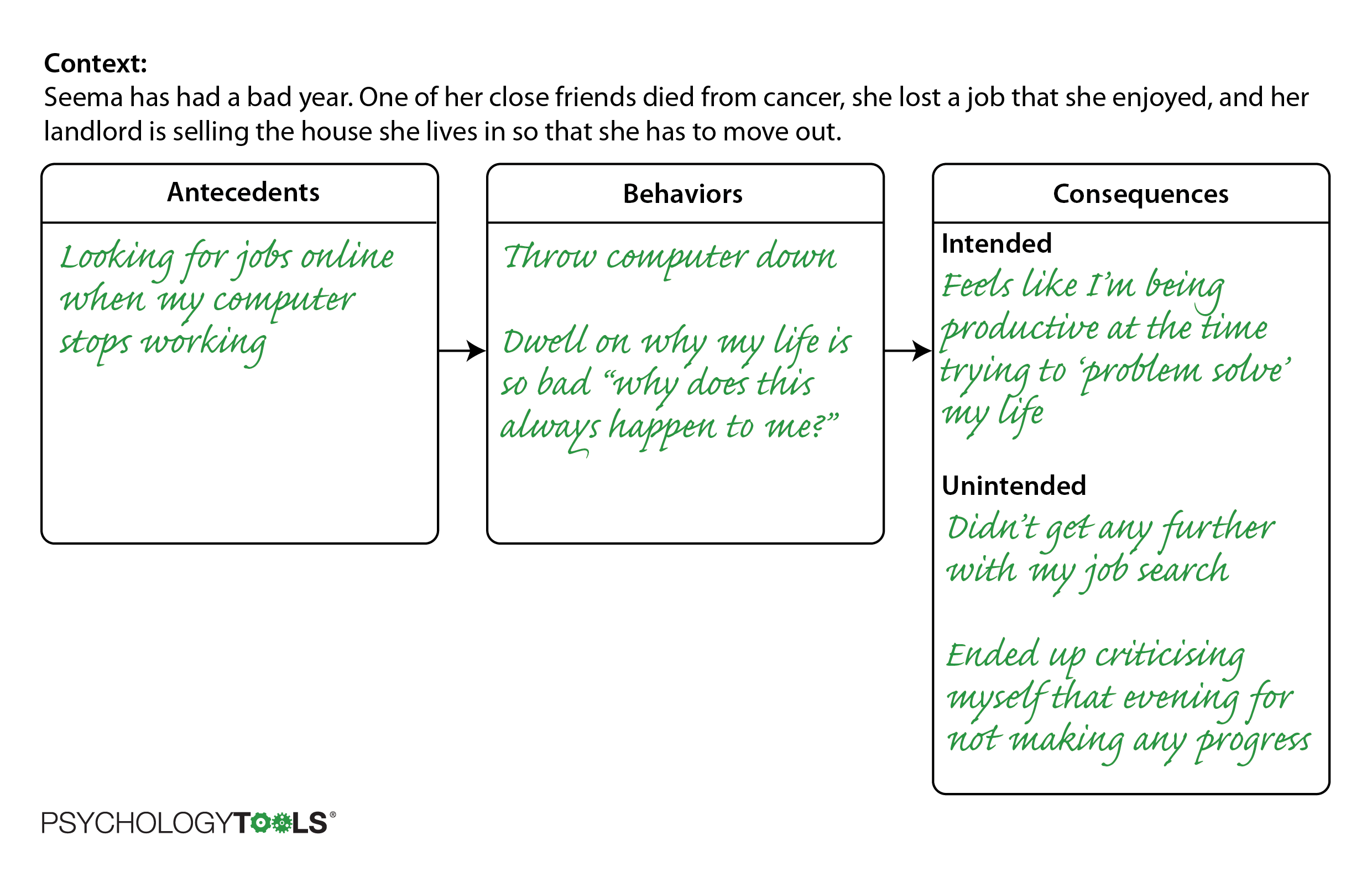

2. ABC model

Another helpful way of dismantling a problem event is to use an A-B-C chart. Instead of looking at one moment in time an A-B-C chart helps us to focus on what happened before and after an (upsetting) event. This can be useful for understanding:

- which things happen in what order; and

- why a problem keeps coming back or has got worse over time.

A stands for Antecendents. You can think of these as ‘triggers’, the ‘thing that happened before’, or ‘what set the problem off ’

B stands for Behaviors. This is how you reacted. This can include emotional reactions, observable behaviors (e.g. “I ran away”), or covert behaviors (e.g. “I told myself off for being so stupid”)

C stands for consequences. What happened as a result of my behavior? How did I feel? Did it affect how other people react towards me? It is often helpful to think separately about short-term and long-term consequences.

Seema has been feeling extremely down. Her family doctor referred her to a psychologist when she broke down in tears during one of their consultations. Seema’s psychologist used an A-B-C chart to explore what was happening around some of Seema’s self-reported lowest moments.

Figure 4.11: An A-B-C chart of one of Seema’s moments of frustration.

This A-B-C chart helped Seema and her therapist to understand that she used rumination as a way of trying to solve her problems. It made her feel productive in the short term, like she was actively trying to solve her problems, but had the unintended effect of exposing her to self-criticism. It was making her feel worse!

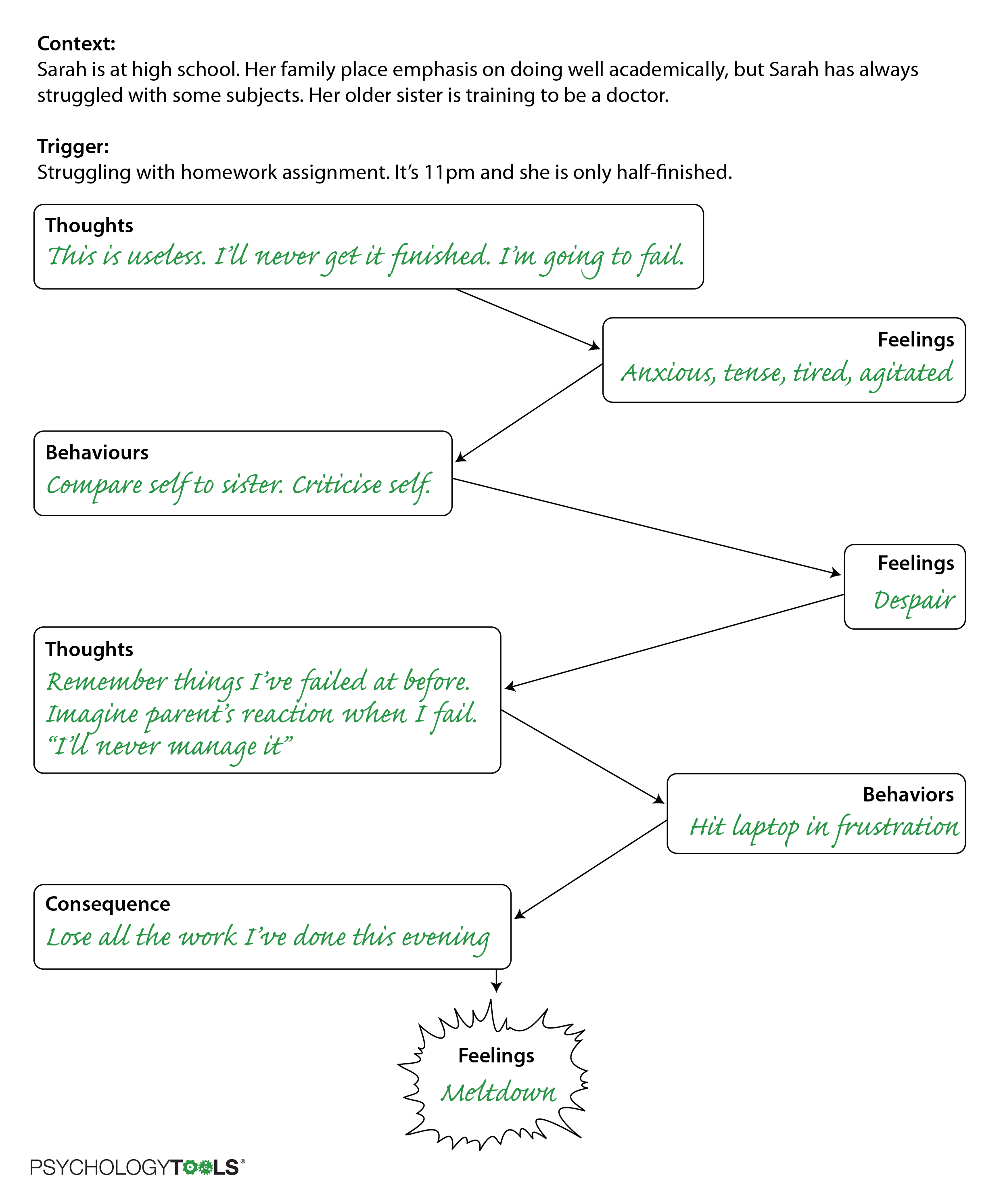

3. Sequence model

Sometimes it can be helpful to understand a problem as a sequence of events. This can be helpful when:

- a sequence is more complicated, or too complicated to fit into the previous models; or

- when searching for points where the ‘chain can be broken’ (moments where we could have taken a different action that would have lessened our pain).

Sarah was brought to therapy by her parents because she had “not been herself” for some months. They felt that she had been angry and ‘snappy’, and Sarah said that she didn’t feel good enough and was often tearful. Together Sarah and her therapist explored some of the recent times that she had felt angry or frustrated, and drew some sequences on a piece of paper.

Figure 4.12: A sequence that Sarah and her therapist identified which ended in a ‘meltdown’.

By monitoring sequences like these it became apparent that Sarah often compared herself unfavorably to other people. She and her therapist experimented by having Sarah consciously choose to make different kinds of comparisons and noticing the effects. With Sarah’s permission she also spoke separately to Sarah’s parents about where Sarah might have developed her ideas about self-worth being tied to academic perormance. Sarah and her parents made other changes that allowed Sarah to pursue some of her creative interests.