What is CBT?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is an effective form of psychological treatment that is practiced by many thousands of therapists worldwide. CBT theory suggests that our thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and behavior are all connected, and that what we think and do affects the way we feel. Thousands of research trials have demonstrated that CBT is an effective treatment for conditions from anxiety and depression to pain and insomnia. It is helpful across the lifespan – children, adolescents, adults, and older adults can all benefit. CBT is flexible too – it has been proven to be effective in face-to-face, online, and self-help formats.

The basics of CBT

There are many different types of psychological therapy and each is grounded in its own theory and assumptions about how people ‘work’. There are a number of key insights in the cognitive behavioral therapy model which help to distinguish it from other therapies. These ideas are the foundations upon which cognitive behavioral understandings and treatments have been built. Some definitions of CBT can help to clarify what makes it unique.

Cognitive behavioral therapies, or CBT, are a range of talking therapies based on the theory that thoughts, feelings, what we do and how our body feels are all connected. If we change one of these, we can alter the others. When people feel worried or distressed, we often fall into patterns of thinking and responding which can worsen how we feel. CBT works to help us notice and change problematic thinking styles or behavior patterns so we can feel better. CBT has lots of strategies that can help you in the here and now. British Association For Behavioural & Cognitive Psychotherapies

Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) is a time-sensitive, structured, present-oriented psychotherapy that helps individuals identify goals that are most important to them and overcome obstacles that get in the way. CBT is based on the cognitive model: the way that individuals perceive a situation is more closely connected to their reaction than the situation itself. Beck Institute

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) helps people identify and change thinking and behavior patterns that are harmful or ineffective, replacing them with more accurate thoughts and functional behaviors, It can help a person focus on current problems and how to solve them. It often involves practicing new skills in the “real world”. American Psychiatric Association

CBT is about meanings

CBT is fundamentally about the meanings which people make of their experiences. CBT is often misrepresented as being concerned with ‘fixing’ faulty thought processes, being ‘rational’, or only working with ‘surface’ issues: but all of these are mischaracterizations. As we live our lives we interpret what is going on around us: we form beliefs and understandings. These meanings affect how we actually perceive the world. Sometimes our beliefs are distressing to us and can lead to unhelpful ways of acting. The role of a CBT therapist is to help their clients to understand and examine their beliefs: to help them to make sense of meanings. Tamara suffered from obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and is a good example of how CBT can be used to unravel meanings.

Shortly after Tamara had her first child she began to experience unwanted intrusive thoughts about harming her baby. She took this to mean that she was a bad and dangerous person. She felt terribly ashamed and frightened, tried to push the thoughts away, and made her partner do most of the childcare in case she caused harm to her baby. Tamara eventually summoned the courage to tell her therapist about the thoughts she had been having. Her therapist helped her to understand that intrusive thoughts are extremely common and entirely normal. Over time Tamara came to understand that her thoughts were precisely the sort that a person who really cared about her baby and felt responsible for it’s safety would have – a truly bad and dangerous person would not worry like she did about the baby’s wellbeing. This change in perspective really helped Tamara. She no longer felt frightened to care for her son and was able to enjoy being a mother.

Appraisals matter

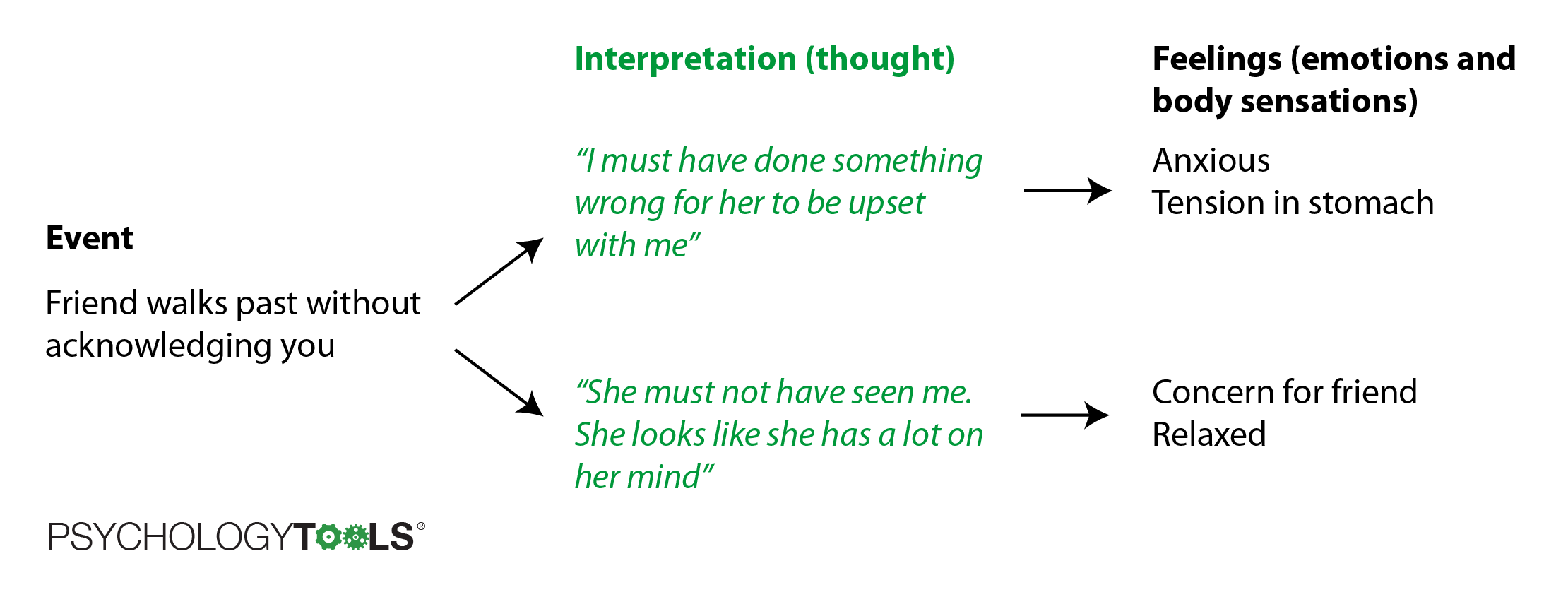

The insight of the CBT model is that it is not events that bother us. Instead, it is the way that we interpret events – the meaning that we give to them – that gives rise to our feelings. This explains why two people experiencing the same event can react in completely different ways. Let’s consider an example:

Figure: How we interpret events determines how we feel about them.

The first interpretation personalizes the events (“What have I done wrong?”) and results in feelings of anxiety. The second interpretation understands the friend’s behavior in more neutral terms and leads to a different outcome.

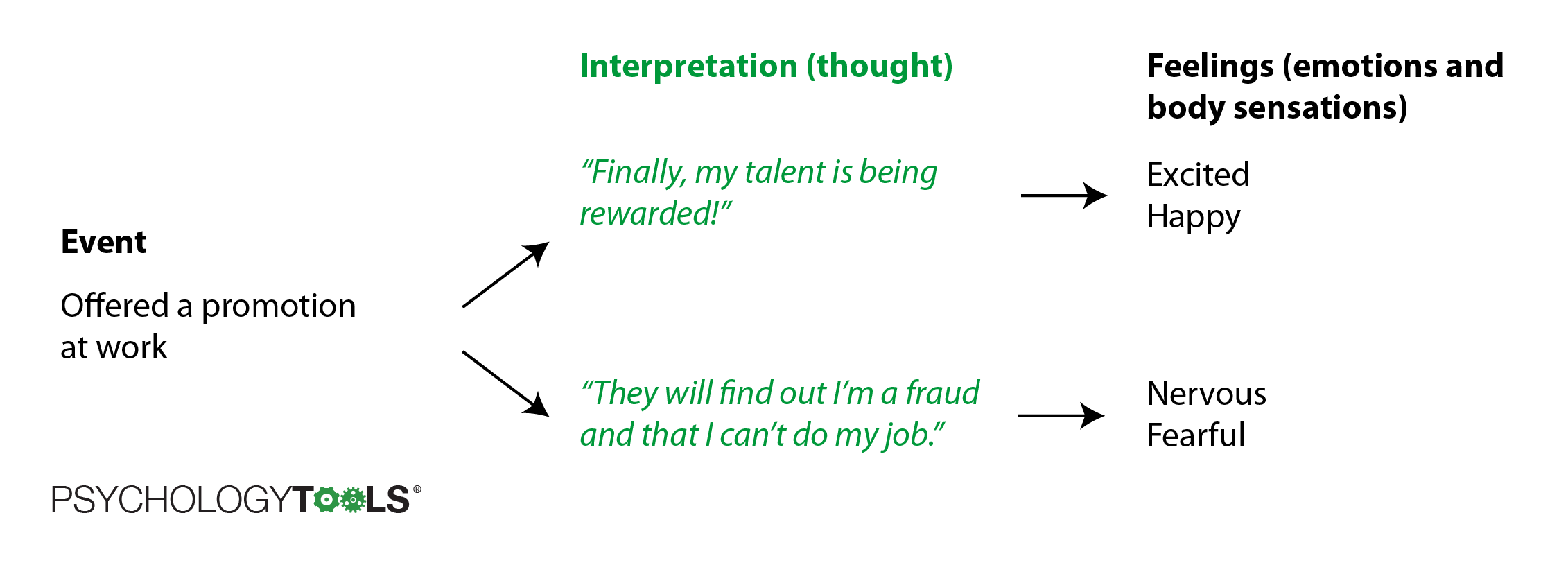

Figure: Another example of how interpreting events determines how we feel about them.

The first interpretation here is an excited one – the offer of a promotion is viewed as a welcome opportunity. The second interpretation is less positive – the person offered a promotion is making a catastrophic prediction about what is likely to happen and the result is anxiety.

This idea about how our interpretation of events matters is not new. Nearly 2000 years ago the Greek philosopher Epictetus said:

“Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.” Epictetus [1]

Shakespeare said something similar in 1602:

“There is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so.” Shakespeare [2]

It may not be a new idea, but it is a powerful one. It explains why some people are pleased when given the opportunity to sing in front of a crowd (“At last, my talent will be recognized!”) when other people would be terrified at the prospect (“I will make a fool of myself and everyone will laugh at me!”). It can explain why some people often feel very anxious (perhaps they have a habit of interpreting situations as threatening) or very sad (perhaps they have a habit of interpreting situations very negatively).

It’s a hopeful idea too: although we may not always be able to change the situations in which we find ourselves (or the people we meet), we are in charge of how we interpret events. The attitude we bring to a situation, and the perspective we choose to take, determines how we feel. Viktor Frankl, a survivor of the Nazi death camps, said this most powerfully:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.” Frankl [3]

Thoughts, feelings, body sensations, and behavior are connected

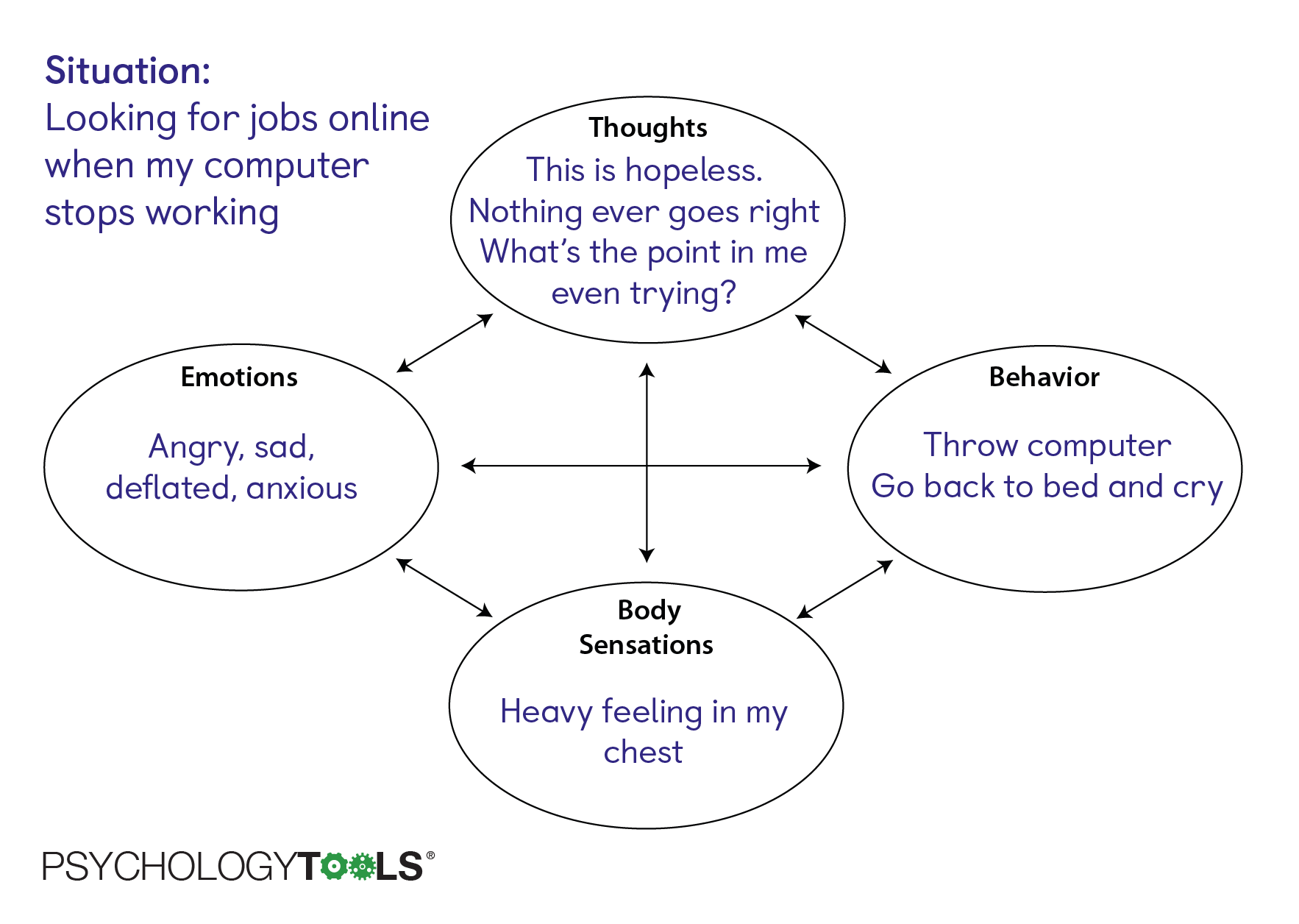

Another important part of cognitive behavioral theory is that our thoughts, feelings, body sensations, and behavior are all inter-related and can affect one another. Things that we do (or things that happen to us) can affect what we think, which can in turn affect how we feel. If you have ever felt poorly with an illness, then you might have had the experience where your body feelings and emotions made you see the world in a ‘bleaker’ or more ‘catastrophic’ light. CBT therapists have lots of ways of representing the relationships between our attention, perception, thoughts, feelings, and behavior. One traditional way of representing how thoughts, feelings, and behavior interact is with a ‘hot cross bun’ diagram [4].

Figure: Hot cross bun representing thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

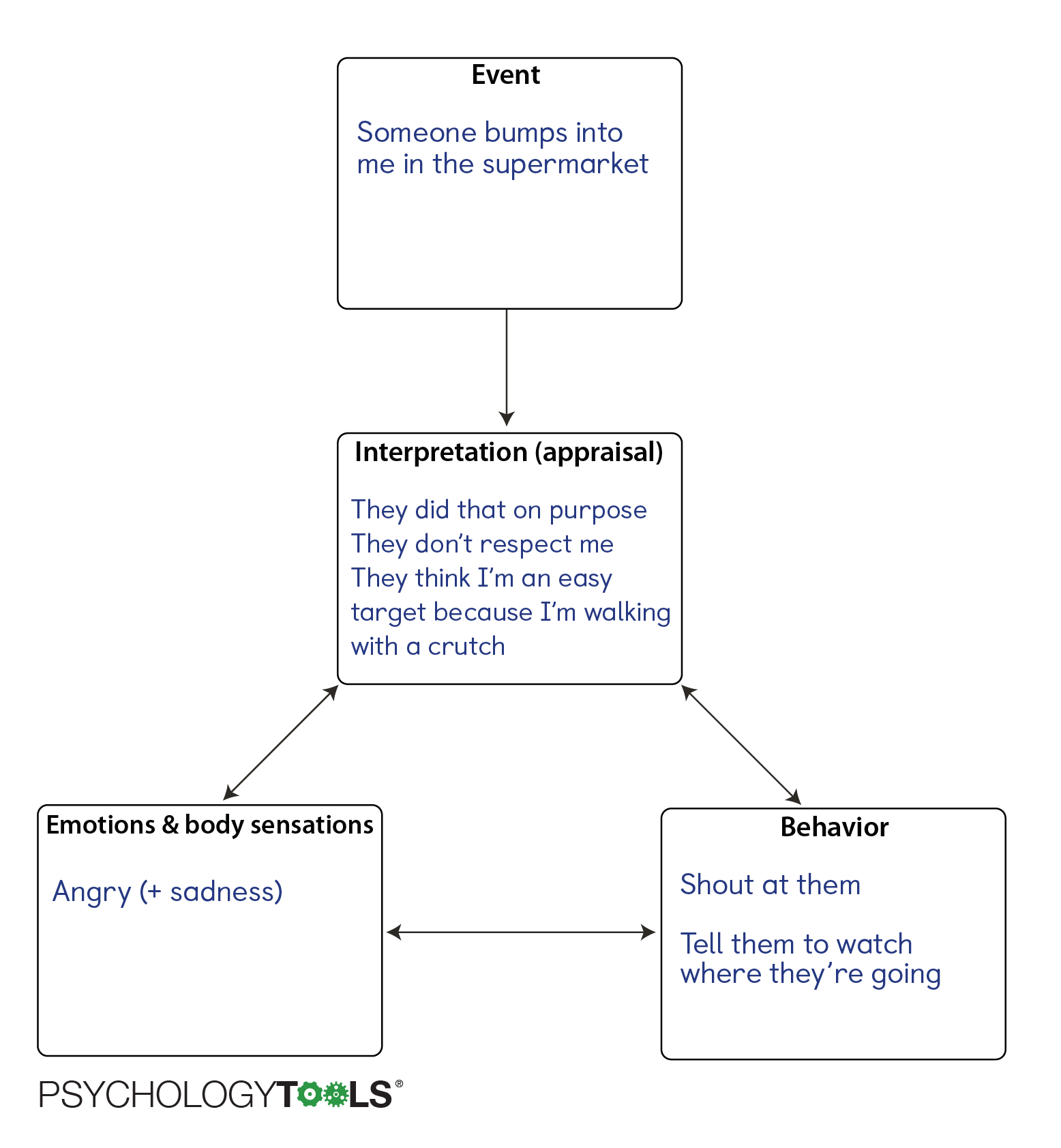

A more helpful way of representing the relationships – one which explicitly captures meanings – is with a cognitive appraisal model.

Figure: We can use a cognitive appraisal model to represent the importance of meanings in the perpetuation of distress.

The inter-relatedness of thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and behaviors can lead to problems:

- A problem at one location can lead to problems at other locations. For example, thinking in an unhelpful way can lead to strong (and perhaps unnecessary) feelings.

- Sometimes the things that we do to cope can inadvertently keep a problem going. For example, avoiding situations which make us afraid can prevent us from learning how dangerous those situations truly are.

The inter-relatedness works to the advantage of the CBT therapist though. If these nodes are inter-related, it means that making a change in one area can cascade into changes in other areas. For example, people who experience panic attacks often interpret normal body sensations in catastrophic ways. These ‘mistakes’ in interpretation lead to powerful and rapidly escalating feelings of anxiety. Cognitive behavioral treatment for panic involves ‘correcting’ these thinking errors, which results in downstream changes in emotion and behavior.

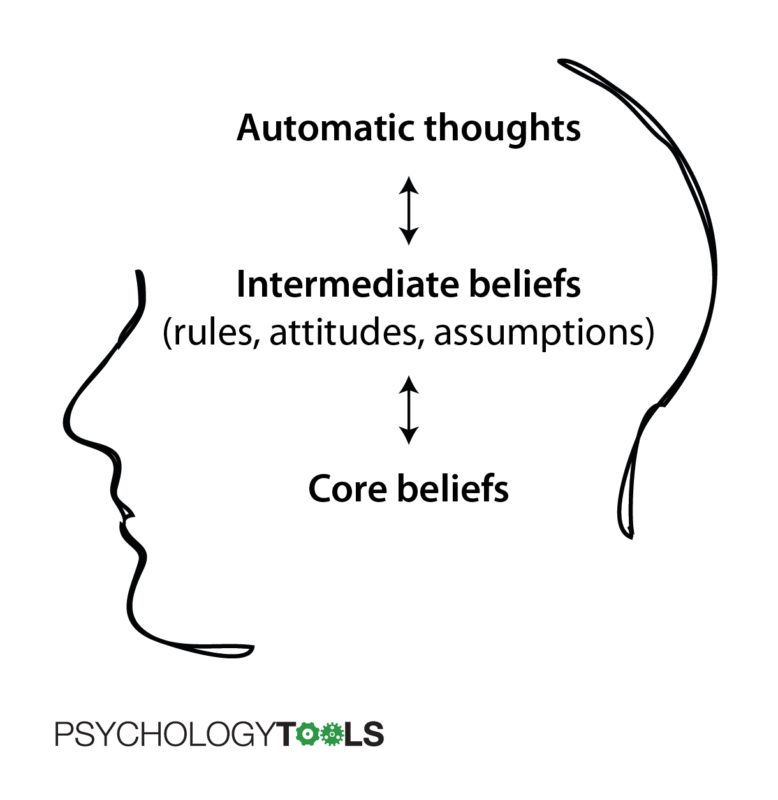

People think on different levels

Cognitive behavioral therapy recognizes that human beings think on different levels: we say that people have different levels of cognition [5]. Cognitive behavioral therapists will help their patients to examine their thinking at all of these levels and will choose therapy techniques which target the most appropriate level.

The level closest to the surface are automatic thoughts. These are thoughts or images which involuntarily ‘pop’ into our minds. They often appear in response to a trigger which can be an event, feeling, or another thought or memory. Automatic thoughts can be accurate (in which case CBT therapists would tend to leave them alone), or they can be biased (in which case they may merit further discussion). Some examples of automatic thoughts include:

- Fails to complete a task > “That was pathetic”

- Talking to a girl I like > “She’ll think I’m an idiot”

- Waiting to demonstrate my work > Mental image of myself failing and being humiliated, others laughing at me

The deepest level of cognitions are our core beliefs. These are often unspoken and may never have been verbalized. We often hold core beliefs as ‘truths’ about ourselves, the world, or other people, but it is important to remember that they are opinions and not facts. We are not born with them, but rather they are the product of our life experiences. They can be thought of as our implicit answers to the question “What has life taught you [about yourself, other people, or the world]?”. Core beliefs often take the form of ‘absolute’ statements. Examples of some negative core beliefs include:

- I am useless / unlovable / stupid

- Other people are critical / cruel / uncaring

- The world is cold / uncaring / unfair

The middle level of cognitions are intermediate beliefs, which often take the form of rules and assumptions. These can often be phrased in the form of “If… then” statements or contain the tell-tale words ‘should’ or ‘must’. We may hold on to our rules or assumptions as ways of preventing the worst consequences of our core beliefs from coming true. Examples of rules and assumptions include:

- If I work hard then no-one will find out how useless I am

- Everyone around me must be happy or I have failed

- I must always be on my guard or else I will be hurt

It is important to recognize that cognitions at different levels interact: the kinds of automatic thoughts that we have are often determined by the kinds of core beliefs that we hold (in fact, therapists often look for patterns in automatic thoughts in order to take educated guesses about what core beliefs their patient holds). For example, when confronted with an ambiguous situation where they may have been let down by a friend, the person who holds the core belief “I am unlovable” is more likely to have an automatic thought “I don’t matter to them”. Similarly, when confronted with an ambiguous situation where other people might give good or bad feedback, the person who holds the core beliefs “I’m stupid” and “Other people are critical” is more likely to have the automatic thoughts (predictions in this case) “They’ll think I’m an idiot” and “They’ll make my life hell”. Cognitions at any of the levels can be more or less helpful – CBT therapists will be looking to identify thoughts, beliefs, or rules that are potentially self-defeating.

Thinking can be biased

Cognitive behavioral therapy recognizes that any of our thoughts, beliefs, or rules can be more or less accurate ways of perceiving the world. A thought can be positive “I did well” or negative “I did badly”, but this is less important than whether it is accurate or inaccurate. Despite what we might prefer, it is unavoidable that bad things will happen to all of us. Trying to avoid every negative event, thought, or emotion is a losing battle and would in any case be counterproductive. More important is that our thinking can be inaccurate. And because our feelings are influenced by the way we think, we often experience negative emotions because we believe inaccurate things – it is as though we feel bad because we are lying to ourselves! Thoughts can become biased for many reasons:

- We are fed incorrect information. A child may come to believe something bad about themselves because they are suggestible and because they don’t have an accurate view of how the world works. If a caregiver repeatedly gives them the message that they are not loved, then they may come to believe that they are unlovable.

- We ‘think fast’ and take shortcuts. Human beings are not robots and we take shortcuts and make mistakes in our thinking. The psychologist Daniel Kahneman described how these shortcuts are ‘hardwired’ in his book Thinking fast and slow.

- Beliefs perpetuate themselves. We may pay attention in biased ways which serves to maintain our biased thinking. If we think we are stupid, then we are more likely to pay attention to times that ‘prove’ this belief and may ignore contradictory evidence.

People’s thinking becomes biased in characteristic ways. In Beck’s early work on depression he recognized that “even in mild phases of depression, systematic deviations from realistic and logical thinking occur” [6]. Four of the ‘cognitive distortions’ that Beck identified early on included:

Arbitrary interpretation which describes the process of “forming an interpretation of a situation, event, or experience when there is no factual evidence to support the conclusion or when the conclusion is contrary to the evidence”. An example of arbitrary interpretation would be having an interaction with a shopkeeper and having the thought “they think I’m worthless”.

Arbitrary interpretation which describes the process of “forming an interpretation of a situation, event, or experience when there is no factual evidence to support the conclusion or when the conclusion is contrary to the evidence”. An example of arbitrary interpretation would be having an interaction with a shopkeeper and having the thought “they think I’m worthless”.

Selective abstraction which describes the process of “focusing on detail taken out of context, ignoring other more salient features of the situation, and conceptualizing the whole experience on the basis of this element”. An example of selective abstraction would be receiving a ‘B+’ grade on a piece of schoolwork, paying particular attention to a comment about how it could be improved, and thinking “I did badly”.

Selective abstraction which describes the process of “focusing on detail taken out of context, ignoring other more salient features of the situation, and conceptualizing the whole experience on the basis of this element”. An example of selective abstraction would be receiving a ‘B+’ grade on a piece of schoolwork, paying particular attention to a comment about how it could be improved, and thinking “I did badly”.

Overgeneralization describes individual’s patterns of “drawing a general conclusion about their ability, performance, or worth on the basis of a single incident”. An example of overgeneralization would be a father noticing their three-year-old child pushing another child in the playground and thinking to himself “I’m a poor parent because he’s a rude child”

Overgeneralization describes individual’s patterns of “drawing a general conclusion about their ability, performance, or worth on the basis of a single incident”. An example of overgeneralization would be a father noticing their three-year-old child pushing another child in the playground and thinking to himself “I’m a poor parent because he’s a rude child”

Magnification and minimization describe “errors in evaluation which are so gross as to constitute distortions … manifested by underestimation of the individual’s performance, achievement, or ability, and inflation of the magnitude of his problems and tasks … It was frequently observed that the patients’ initial reaction to an unpleasant event was to regard it as a catastrophe”. An example of magnification would be receiving a telephone call from a friend to say they will be late to a meet-up and thinking “well, the evening is ruined”.

Magnification and minimization describe “errors in evaluation which are so gross as to constitute distortions … manifested by underestimation of the individual’s performance, achievement, or ability, and inflation of the magnitude of his problems and tasks … It was frequently observed that the patients’ initial reaction to an unpleasant event was to regard it as a catastrophe”. An example of magnification would be receiving a telephone call from a friend to say they will be late to a meet-up and thinking “well, the evening is ruined”.

To learn more about the ways in which people’s thinking can become biased read our Psychology Tools guide to unhelpful thinking styles.

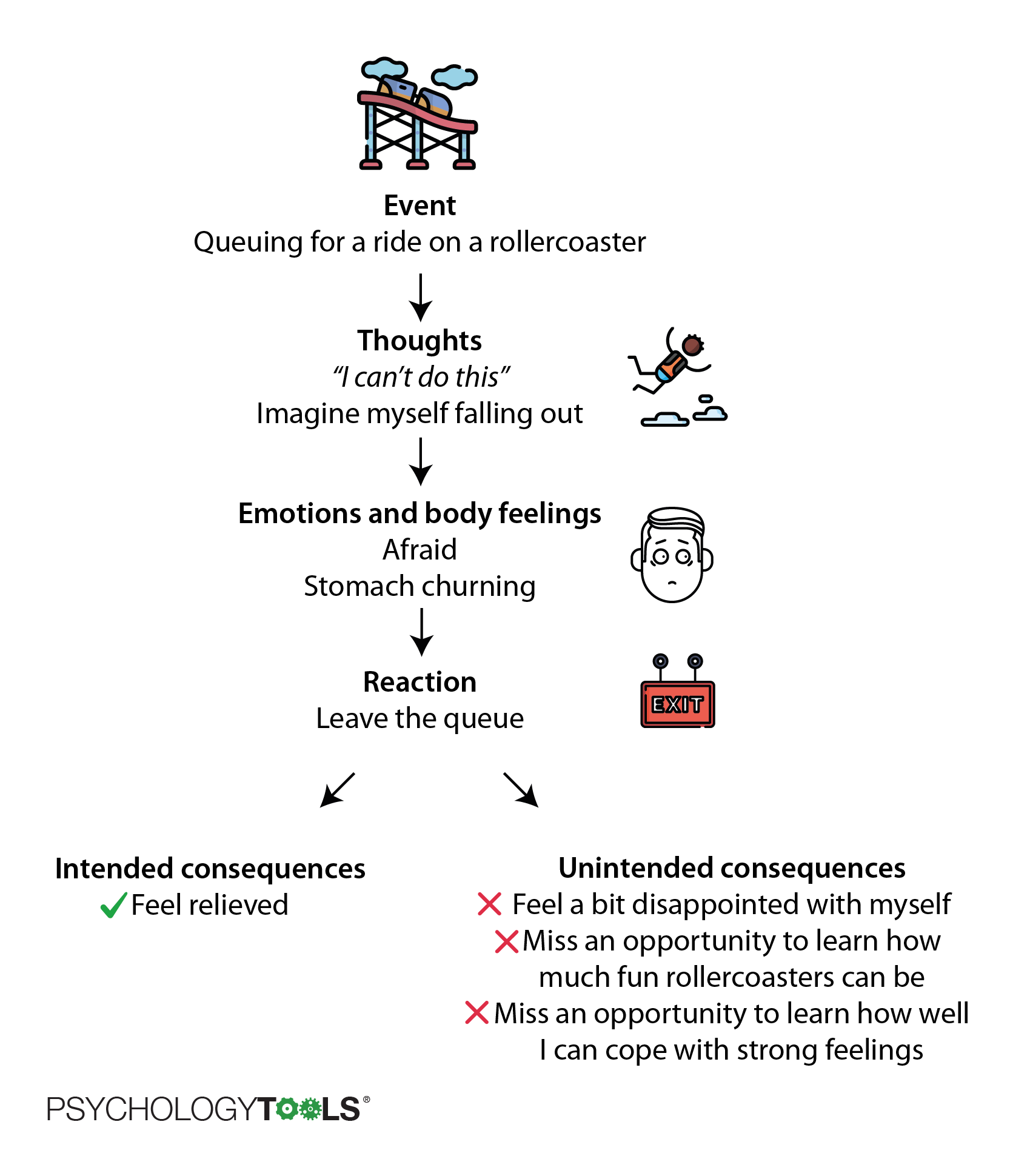

Things that we do can have unintended consequences

The physicist Isaac Newton’s third law of motion states that “Every action has an equal and opposite reaction” [7]. Our actions are similar – everything that we do has a consequence. Some consequences are intended, but others are not. A common step in CBT is to ask the question “What were the consequences of acting that way?”. You might have escaped a frightening situation with the (intended) consequence that you felt safer. But perhaps some unintended consequences were that you learned that it feels good to escape and escaping became your ‘go to’ strategy for handling tricky situations. Therapists who use CBT are trained to pay particular attention to any sequences that appear to get stuck in a loop or jammed (where an action feeds back to cause more of the problem).

Figure: Our actions have intended and unintended consequences.

For example, if you suffer from depression you might spend much of the time feeling sad, low, and demotivated. When you feel that way it is difficult to do the things that used to give you pleasure, and so you might avoid situations with the intended consequence of conserving your energy. Unfortunately, the unintended consequence of behaving this way is that you have fewer opportunities for good things to happen to you, and the result is that you stay depressed.

CBT is a ‘doing therapy’

CBT is a great way of understanding of what is keeping a problem going and when we are armed with that information our job is to take action in order to get it ‘unstuck’. What makes CBT different is that it is not just a ‘talking therapy’. Psychologists have found that to be really helpful, a therapy has to help you to make changes in your life and so it is better to think of CBT as a ‘doing therapy’. CBT therapists can choose from a huge range of strategies and techniques to promote change. Some of the most common CBT strategies for change are:

- Facing your fears. Exposure is an old behavior therapy technique and is one of the most effective treatments for anxiety. CBT therapists use exposure in a variety of ways to help their patients overcome fears.

- Testing your beliefs and assumptions. The CBT models says that our beliefs and assumptions – the meanings we make of the world around us – are responsible for our suffering. CBT therapists help their patients to find out how accurate their assumptions and predictions are, and to create more accurate and helpful ways of thinking.

- Replacing unhelpful habits. Often, with the best of intentions, we develop unhelpful habits. Sometimes these are called ‘safety behaviors’ and they can keep problems going. Psychologists often help their patients to find out whether these old habits are helpful or harmful and help them to develop more life-affirming habits.

- Learning new skills. Sometimes our problems persist because we just don’t know how to live any different. CBT can help you to live a richer life by learning new skills.

CBT works

What is CBT used for?

CBT was originally developed by Aaron Beck as a treatment for depression, but it was quickly adapted to treat a wide range of mental health conditions. Emotional problems that CBT is used to treat include:

- Depression

- Anxiety (including generalized anxiety disorder, panic attacks and panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder)

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and dissociative disorders such as depersonalization and derealization

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

- Eating disorders including anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa

- Personality disorders

- Psychosis and unusual beliefs

- Low self-esteem

- Physical health problems including chronic pain, tinnitus, and long-term conditions

- Medically unexplained symptoms including fatigue and seizures

How effective is CBT?

CBT is an evidence-based form of therapy which means that researchers try to discover what components of therapy work, for which problems, and why. Individual therapy sessions also pay close attention to evidence: clients in CBT are typically encouraged to set personal goals (e.g. “If I was feeling less anxious I would be able to do my shopping by myself without needing to escape”) and then record data (evidence) about whether these goals are being met.

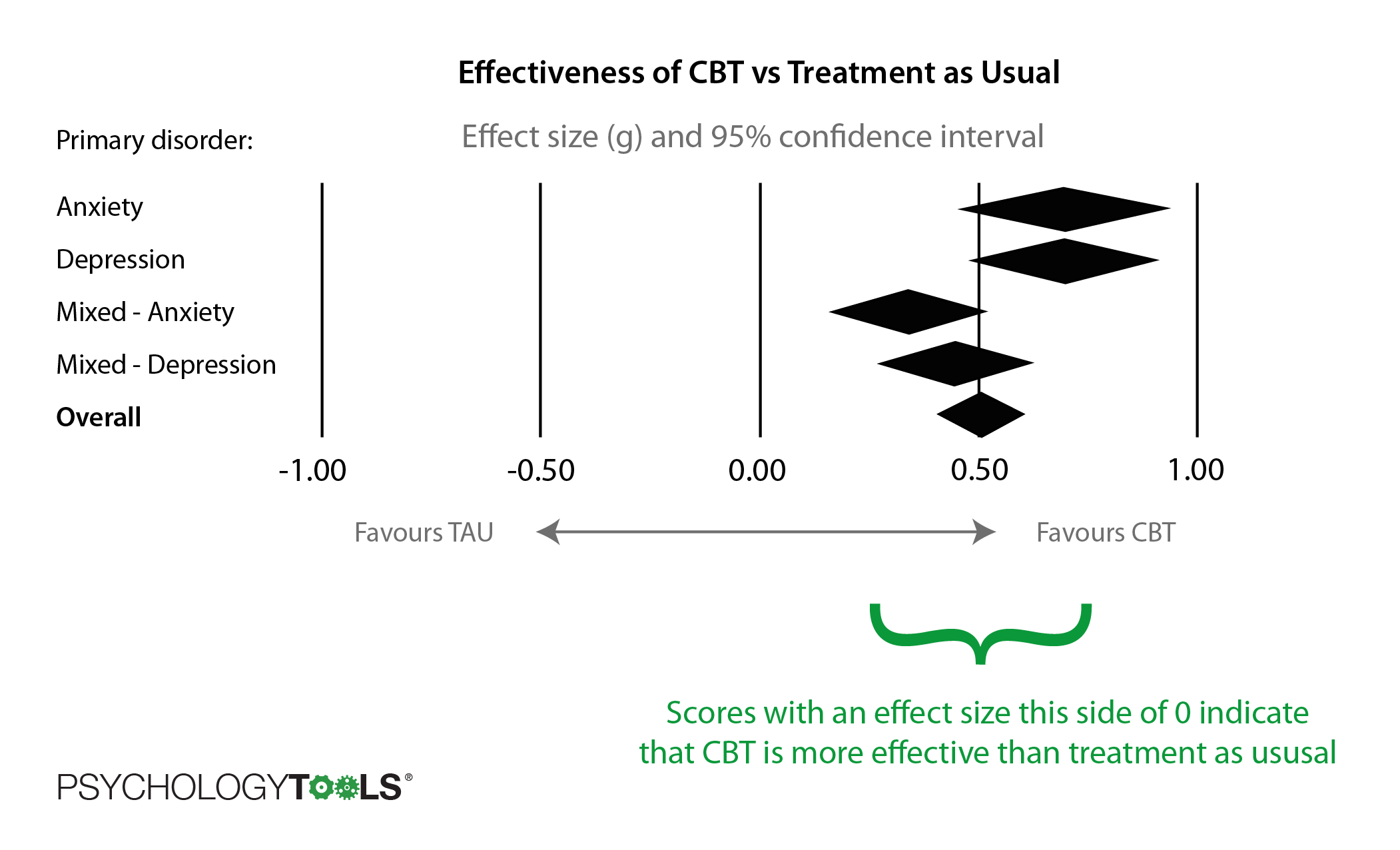

When we ask “how effective is CBT?” we really mean “what is it effective for?” and “effective compared to what?” We also need to consider “how often do these conditions get better by themselves?”. One way that researchers address these questions is by conducting randomized controlled trials (RCTs), where different treatments are carefully and systematically compared to one another. The same process is used in medicine to test the safety and effectiveness of new drugs. Over the past few decades thousands of such studies have examined CBT and researchers can now combine the results of these RCTs into ‘meta-analyses’ to show, in even more reliable ways, which treatments work. The graph below shows the result of a meta-analysis of CBT that was published in 2015 [8]. The results are from 48 studies that compared CBT with ‘treatment as usual’ for nearly 7000 people with anxiety, depression, or mixed anxiety & depression. The results show a clear effect in favour of CBT – more people get better when they receive CBT compared with their usual treatment.

Figure: The effectiveness of CBT vs treatment as usual (TAU).

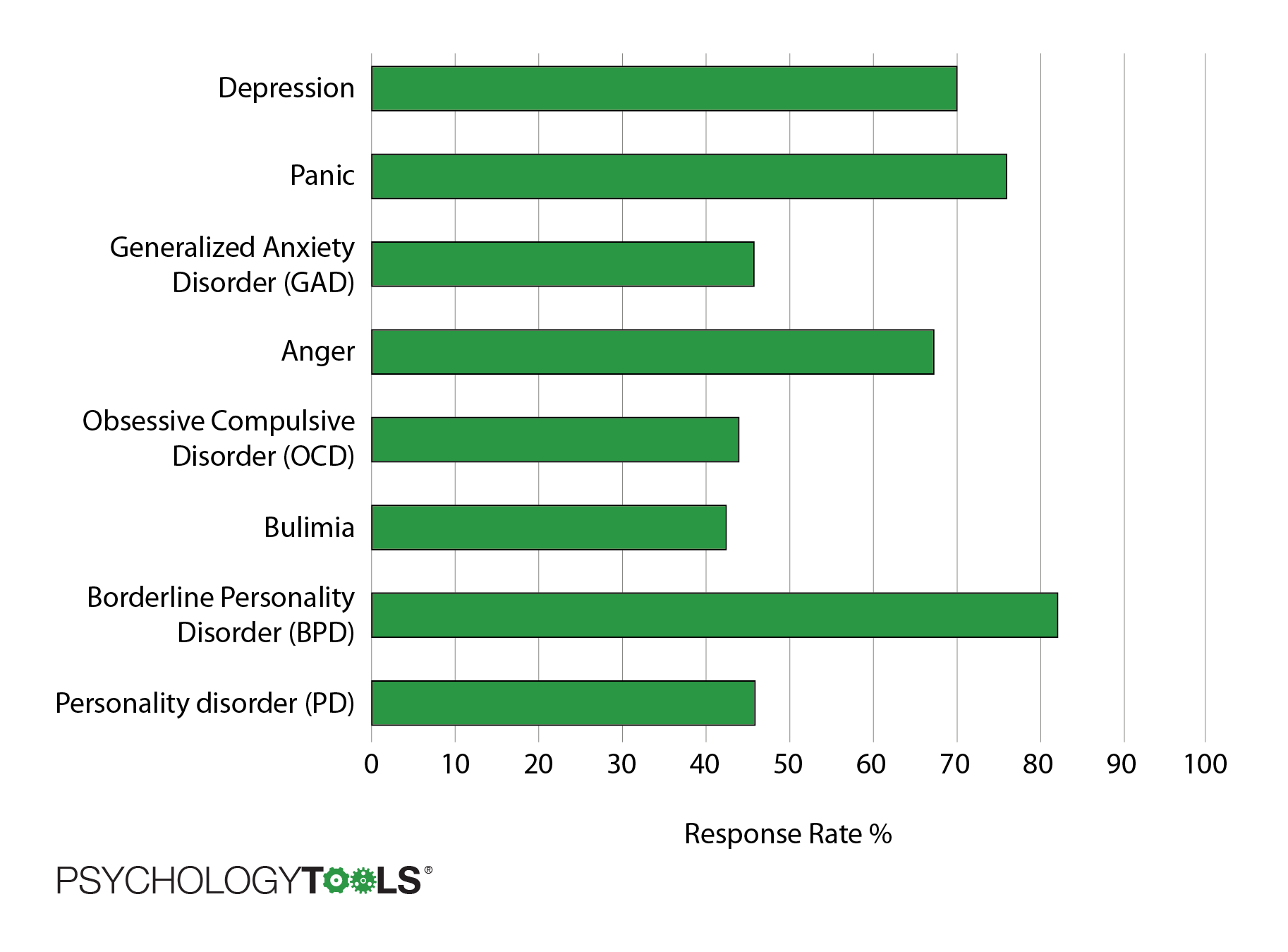

Another way to measure how effective CBT is for treating psychological problems is to look at ‘response rates’. Somebody is said to ‘respond’ to a therapy if their symptoms have improved significantly by the end of treatment. A study that compared 106 meta-analyses was published in 2012 [9]. The graph below shows the response rates for CBT across a wide variety of conditions.

Figure: Response rates for CBT for a variety of conditions (higher is better).

These results look good, but you might be thinking “What do the results look like for the alternatives?” Where adequate data were available, that same study also compared the response rates of CBT to other ‘genuine’ forms of therapy or treatment as usual. CBT for depression was at least as effective as medication or other forms of psychotherapy, and more effective than treatment as usual. CBT for anxiety was typically superior to other forms of genuine and placebo therapies and was judged to be a “reliable first-line approach for treatment of this class of disorders”.

Figure: Response rates for CBT compared to other treatments, or treatment as usual.

The message from these reviews is that for many conditions CBT is as effective or more effective than other genuine forms of therapy and is typically better than ‘treatment as usual’ (which often includes medication or check-ups with doctors) or doing nothing. In recognition of its effectiveness there has been a nationwide push by government in the United Kingdom to make CBT therapies available for free to everyone who needs them.

The history (and future) of CBT

What came before CBT?

To really understand the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach we need to know where it came from and what it was developed in reaction to. CBT emerged in the 1960’s, in an era when psychological therapies were much less established than they are today. Radical new ideas and theories about psychological functioning were emerging and there was much less evidence for the effectiveness of each approach. This meant that therapists were experimenting with new techniques. The dominant models at the time were psychoanalysis and behaviorism.

The clinical practice of psychoanalytic psychotherapy was established by Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth century. Psychoanalysis, and a shorter variant called psychodynamic psychotherapy, are still practiced today. The central proposal of psychoanalytic theory is that we have a dynamic unconscious whereby much of our mental life occurs outside our conscious awareness. Psychoanalysis proposes that some of our thoughts and feelings are kept outside of our awareness by our ‘defenses’ but can still affect our behaviors, attitudes and experiences – which can lead to problems. Resolution is said to come from bringing these difficult thoughts and feelings into our conscious awareness. Perhaps the aspect of psychoanalytic theory that has gained the most traction concerns how peoples’ early relationships with caregivers (their attachment relationships) affect how they form relationships for the rest of their lives. ‘Attachment theory’ is the foundation of many modern approaches to psychotherapy. Psychoanalysis has been criticised on the grounds that many of its claims cannot be tested and that they are not falsifiable. Nevertheless, psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy are still practiced today despite no longer being the dominant model in mental healthcare.

Behaviorism is an approach grounded in the scientific study of learning and behavior. Compared to psychoanalysis its practice is much more empirical, experimental, and scientifically robust. Early behaviorist researchers including John Watson and Ivan Pavlov discovered the concept of classical conditioning and other ideas about how animals and humans learn. B. F. Skinner is famous for his discovery of operant conditioning – the idea that our behavior can be shaped by contingencies (what comes before and after). An important part of these psychologists’ research explored how fears are learned. These ideas were applied clinically as ‘behavior therapy’ by luminaries including Joseph Wolpe and became the foundation of fear reduction techniques that are still in use today. Behavior therapy led to great progress in the treatment of anxiety disorders and these concepts are still applied today, but therapists found that it had less to offer in the treatment of conditions such as depression and psychosis.

Who developed CBT?

Aaron T. Beck is responsible for the development of the form of CBT that is most commonly practiced today. No history of CBT is complete without mention of Albert Ellis who was also developing a form of cognitive therapy at the same time as Beck. Ellis’ work became Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT) and shares many similarities with CBT.

Figure: Aaron T. Beck developed cognitive therapy.

Aaron Beck was a psychiatrist who was working at the University of Pennsylvania in the 1960’s. He had been trained in psychoanalysis but became disillusioned with the approach of using free association and began to experiment with more direct techniques. Working with depressed clients he found that they experienced streams of negative thoughts which he called ‘automatic thoughts’. He found that he could work effectively with his client’s thoughts and beliefs – the meanings that they created as they came to understand the world around them. He published the seminal Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders in 1975 and has since authored or co-authored 25 books and over 600 articles.

Simultaneously, Albert Ellis was working on a form of cognitive therapy descended from the Stoic idea that it is not events that distress us but the meaning we give to them. Ellis’ ideas were developed as Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT). There is significant overlap between both approaches but it is arguably Beckian cognitive therapy that has been more influential.

What types of CBT are there?

CBT has an empirical stance which means that it has changed and developed with the emergence of new scientific discoveries and theoretical advances. Many clinicians and researchers trained with Beck and Ellis and have since gone on to train subsequent generations of therapists, scientists, and scientist-practitioners. Over time CBT has grown to encompass a wide variety of therapeutic practice and modern CBT is best thought of as a ‘family’ of therapies that adapts as scientists make new discoveries about how people ‘work’.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT). DBT was developed by Marsha Linehan for the treatment of people with borderline personality disorder or chronic suicidal behavior. DBT combines cognitive behavioral techniques with mindful awareness and distress tolerance practices.

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). ACT was developed by Steven Hayes in the 1980’s, building on ideas from radical behaviorism. Compared to traditional CBT, ACT places less emphasis on changing (controlling) the content of one’s thoughts, and more emphasis on the relationship that we have with our thoughts. The goal of ACT is to increase psychological flexibility – the ability to Accept your reactions and be present, to Choose a valued direction, and to Take action (ACT).

- Compassion Focused Therapy (CFT). CFT was developed by Paul Gilbert for the treatment of people who experience profound shame and self-criticism, people who often struggle with traditional CBT. It combines an evolutionary understanding of our ‘tricky brains’ with techniques from CBT and Buddhist psychology. CFT aims to help individuals to relate to themselves with self-compassion rather than self-attack.

- Schema therapy. Schema therapy was developed by Jeff Young for the treatment of people with personality disorders and other chronic difficulties. Schema therapy integrates elements from CBT with ideas from attachment theory, object relations theory, and Gestalt therapy. The goal of schema therapy is to help patients to meet their basic emotional needs by changing organized (and ingrained) patterns of thinking and behavior (schemas).

- Mindfulness Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT). MBCT was developed by psychologists John Teasdale, Zinden Segal, and Mark Williams. MBCT combined CBT knowledge and techniques with mindfulness meditation practices. The strongest evidence for effectiveness of MBCT is as a relapse-prevention treatment for people with depression.

- Metacognitive therapy (MCT). Metacognitive therapy was developed by Adrian Wells. MCT focuses on the beliefs that people have about their own thoughts, and about how their own mind works – their metacognitive beliefs. MCT is used to help patients explore the effects of their metacognitive beliefs, and to explore alternative ways of thinking and responding.

Figure: The history and future of CBT. A timeline of what came before and after Beck and Ellis’ cognitive behavioral therapy.

What is CBT like?

Therapists who practise psychological therapies are trained to focus on particular aspects of a person’s experience and to react in particular ways. We can say that every therapy has a different ‘stance’. For example, systemic therapists are trained to focus on the way people relate to one another and on how an individual responds to the actions of other people in their network. Solution-focused therapists’ training leads them to help their clients to stay focused on the future and on potential solutions to current difficulties. Psychodynamic therapists are trained to notice how patterns from early (attachment) relationships are played out in a person’s later relationships. Some important properties of CBT’s stance are that:

- CBT is focused on the here-and-now. CBT theory says that the here-and-now is where our pain and suffering lies: if we are anxious we feel the fear now, and if we are depressed our feelings of sadness or loss are happening now. CBT also recognizes that we might be doing things in the here and now that inadvertently prevent our problems from resolving – if this is the case then an obvious solution is to discover and address these ‘blocks’ as soon as possible. Sometimes CBT is criticized for this here-and-now stance by those who argue that it ignores a person’s past. This is a misunderstanding though. CBT does pay close attention to our personal histories since understanding the origin of problems, beliefs, and interpretations is often essential to making sense of them. That said, the problems are causing pain and suffering in the present – and this is where we have the power to make changes – and so the focus of CBT will frequently return to the present moment.

- CBT is rational. CBT takes the position that human experiences are understandable, and that our feelings are a result of processes that we can make sense of. When they work together a client and CBT therapist will attempt to come to a shared understanding of a problem and, building on that understanding, think of ways to address the problem (a process called case formulation). CBT also promotes a rational approach to thinking: the goal is not to ‘think happy thoughts’ but for our thinking to be balanced and accurate.

- CBT is empirical. CBT was developed from the rigorously scientific behavioral tradition where inputs and outputs were measured and has inherited this empirical approach. One sense in which CBT’s approach is empirical is that treatments are grounded in evidence about what works. Many CBT treatments have been compared to other treatments in large randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These are similar to the ways in which medicines are tested for effectiveness. These studies have demonstrated conclusively that CBT is an effective treatment for a wide variety of conditions. CBT therapists therefore practice evidence-based treatments. CBT is also empirical in the sense that progress within treatment is monitored, with the therapist and client closely observing what is working and what isn’t. On a broad level they might monitor symptoms session-by-session and expect to see improvement over time. On a finer level they will measure things like:

- How much a client believes in a particular thought.

- How much the client believes in that same thought after conducting a within-session experiment.

- How anxious a client feels before and after an experiment.

- CBT is collaborative. CBT therapists make a point of conducting therapy that is collaborative. They will aim for therapy to feel like a journey of exploration where the therapist is ‘beside’ the client instead of one where the therapist is positioned as an expert. One goal of CBT therapy is for the client to become their own therapist. CBT therapists often talk about the goal of therapy being one of making themselves redundant. Their goal is to teach their client all they know, to the point where the therapist is no longer needed.

- CBT is active. CBT therapists are actively engaged in the therapy. They are likely to talk more than clinicians who practice other forms of therapy. This doesn’t mean that CBT is all about telling clients what to do and think but rather that CBT is experimental: the CBT therapist will take the position of “I don’t know the answer to that, but how might we find out?”. They will be actively exploring ways of helping their client to find out for themselves. These methods often include experiments that are conducted in and out of the therapy office or might require going out into the world and seeking input from other people.

- CBT is time-limited and relatively brief. Cognitive behavioral treatments are typically relatively brief, ranging from 6-20 sessions. This doesn’t mean that CBT treatment is any less effective than other forms of therapy – when compared head-to-head against other bona-fide therapies it actually tends to out-perform them. Because CBT is empirically grounded the length of therapy can be guided by whether it is working: is the client meeting the goals that were decided at the start of therapy?

What is CBT like? The process of treatment in cognitive behavioral therapy

A helpful way to illustrate how CBT works is to walk through the steps that a therapist might go through with a client. In face-to-face CBT a therapist may go through some or all of the following stages. Remember that although the process is described here in a linear fashion people and their problems are not straightforward and there is often a ‘dance’ back and forth between the stages.

Stage 1: Assessment in cognitive behavioral therapy

During the first session (commonly the first few sessions) a cognitive behavioral therapist wants to find out what kind of problems are troubling their client. They will also want to explore the client’s goals – what would they want to be different by the end of therapy? CBT therapists will conduct an assessment by discussing some or all of the following:

- Asking open questions to help a client discuss their problems. “Tell me why you’re here”, “What has been troubling you recently?”.

- Making a ‘problem list’ with a client and thinking together about the relative importance of each of the problems. “Now that we have made a list of the things that are troubling you at the moment, could we try to put them in order of how much each interferes with the life you want to lead?”

- Generating specific and measurable goals. This is often achieved by focusing on what behaviors a client might want to change. “What would you be doing differently if this problem wasn’t a problem anymore?”

- Using questionnaires and structured interviews which can assess the presence or absence of symptoms and difficulties. “I’m going to ask you a series of questions about how you have been feeling in the past month and I would like you to answer each question using this five-point scale which goes from ‘never’ to ‘very often’”

- Asking questions about risk including a discussion of current and past suicidal thoughts and actions. “Do you ever have thoughts about hurting yourself or ending your life?”

CBT assessment technique 1: Focus on specific events that happened recently

To understand their client’s problems, therapists who practice cognitive behavioral therapy often begin by paying close attention to specific events that have happened relatively recently. This means that they attempt to identify specific details like “Yesterday when I saw someone who looked like my attacker I was frozen to the spot with terror” rather than “I’m just always feeling so low that I’m not sure it’s worth it anymore”. It can take some work to extract specifics from examples like the latter: when the therapist asked for some more details she was told “When I watched a programme last night on tv about friendships and realized I didn’t have anyone close anymore I felt so sad that I wondered what the point was in my existing”.

The reason that CBT focuses on specific events is because our lives are made up of specific moments all chained together. We live our lives moment-by-moment and feel our feelings that way too. We might tell ourselves stories like “I had the most boring day ever” but chances are that your day was made up of some boring moments, and perhaps some mildly interesting ones too. If we want to pay attention to our thoughts and behaviors, these happen moment-by-moment and we will miss important parts if we gloss over the details.

The reason that CBT focuses on things that are problems now is because problems that happened in the past may no longer be a problem. Even if terrible things did happen in the past, our suffering – what we want to relieve – happens in the present. One of the assumptions that CBT makes is that things happening in the here-and-now (perhaps thoughts, perhaps action) are contributing to that suffering. A final advantage of working on current material is that our memory for it is often better, which means that we can explore it in more detail.

CBT assessment technique 2: Break moments down into helpful components

Once we have identified a specific and relatively recent event, the next job is to break it down into manageable parts. These might include:

- Situation: Who was there? What happened? When did this happen? Where did you experience the problem? (Who? What? When? Where?)

- Triggers: What was happening just before the problem occurred?

- Cognitions: What went through your mind at the time? (This might include thoughts, beliefs, interpretations, predictions, assumptions, memories, images, or a combination of any of these).

- Emotions: What did you feel? (Each of our emotions can typically be described in one word: happy, sad, helpless, angry).

- Body sensations: What feelings or sensations did you notice in your body?

- Actions or responses: How did you respond? What did you do to cope? (This might include overt acts like standing up for yourself, or covert acts like distracting yourself in your mind).

- Context: All the while, we need to hold in mind the context in which an event is happening. For example, if David is having worries about his health then it is relevant and useful to know that he has suffered three bereavements in the past year.

The reason that CBT therapists conduct assessments by breaking events down into components is because a cognitive behavioral approach recognizes that these components are interconnected. One component affects other components in understandable ways. Making sense of these connections is called case conceptualization which we will explore in the next section. Some of the most helpful CBT worksheets and information handouts for psychological assessment include:

- Simple Thought Monitoring Worksheet. Learning to identify negative automatic thoughts is an important skill in CBT. Thought records can be a helpful tool during the assessment phase of therapy to help clinicians identify patterns of automatic thoughts, common triggers, common cognitive distortions, and to make inferences about rules, assumptions, and core beliefs.

- Problem List Worksheet. Identifying problems and goals is an essential part of a cognitive behavioral assessment. It helps the client and therapist to find a focus for therapy and allow the development of a formulation or ‘roadmap’ to recovery. The Problem List worksheet is one way of gathering information about current difficulties, with separate versions for clients and therapists

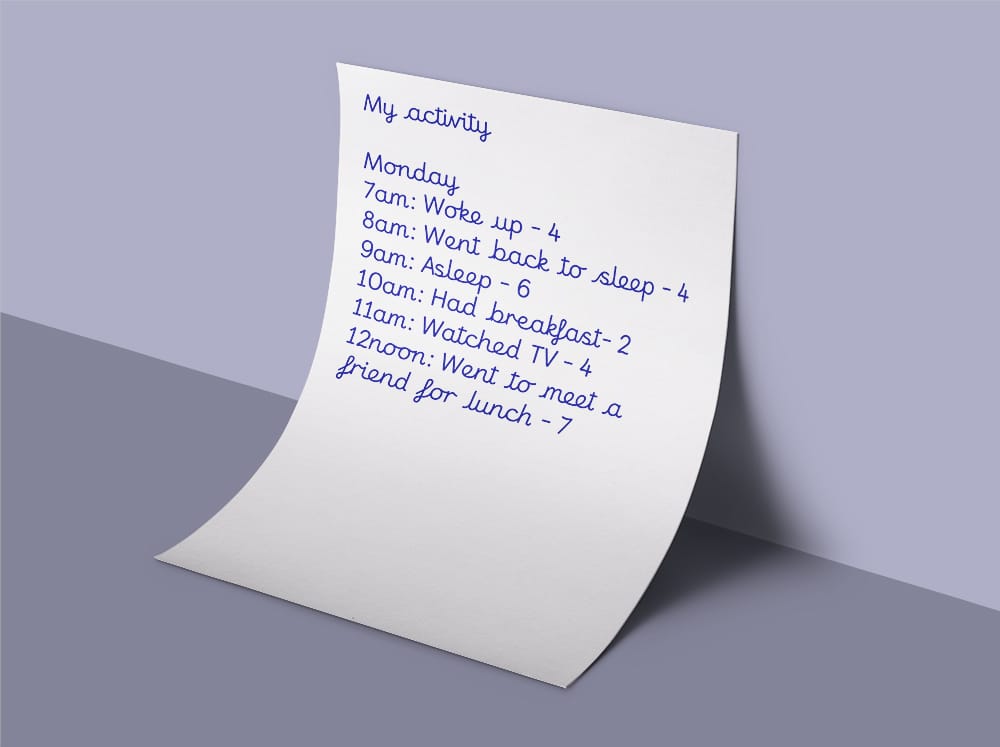

- CBT Activity Diary. Finding out what an individual does and where and when problems occur in their life is a helpful practice during the assessment phase of therapy. An activity diary can be used to monitor an individual’s activity over the course of a day or week. When combined with quick measure of mood (e.g. enjoyment, anxiety) activity diaries can be used to pinpoint situations which merit further investigation.

Stage 2. Case formulation (case conceptualization) in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

It’s one thing to identify a problem but in order to find solutions we need to (1) understand what is keeping the problem going and (2) find some ways to stop it. CBT therapists use a process called ‘case conceptualization’ or ‘case formulation’ to come to an understanding of how a problem operates. A formulation is simply a model or set of hypotheses (educated guesses) about what is going on: an idea about how the pieces fit together. A therapist will form their own hypotheses about what is going on, will share hypotheses with their client, will explore any hypotheses the client has, and will try to find ways with the client of testing whether these hypotheses are accurate. CBT therapists will often draw a case formulation diagram together with their client as a way of ensuring sharing their understanding of what might be happening.

CBT focuses on relationships and consequences

When considering any problem, the therapist will try to gather information about: where and when a problem happens; what kinds of things trigger it; and what thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and behaviors it leads to. The next step is to look for relationships between these components. This is helpful for working out what happened and in what order. As a general rule:

- Anything we notice can trigger our thoughts. Common triggers for our thoughts include events, things around us (sights, sounds, smells), body sensations, other thoughts, or memories. We can also think about anything, so anything can be a trigger for our thoughts.

- Thoughts lead to feelings. A key insight of CBT is that the way that we interpret situations affects how we feel about them. These interpretations can happen quickly and automatically and are affected by other things that have happened in our lives. Remember though, that our automatic thoughts are not always accurate. For example, Tracy had been abused by people who initially showed her kindness. The result was that she came to interpret any kindness as a ‘warning sign’ of impending danger – even when the other people were being genuine and kind.

- Actions lead to consequences. The physicist Isaac Newton’s third law of motion states that “Every action has an equal and opposite reaction”. Our actions are similar – everything that we do has a consequence. Some consequences of our actions are intended, but others are not. A common step in CBT is to ask the question “What were the consequences of acting that way?”. You may have escaped a frightening situation with the (intended) consequence that you felt safer. But perhaps some unintended consequences were that you learned that it feels good to escape and escaping became your ‘go to’ strategy for handling tricky situations. Analyzing consequences helps CBT therapists to understand why problematic patterns persist for longer than we might otherwise expect.

CBT focuses on what keeps a problem going

A fire needs three things to start: heat, fuel, and oxygen. As long as those things are present the fire will keep on burning. We say that a fire’s maintaining factors are heat, fuel, and oxygen. With this knowledge, firefighters can choose which maintaining factor to target. Depending on the type of fire they are faced with they may decide to:

- Remove the oxygen by spraying the fire with; CO2; or

- Remove the fuel available to a forest fire by creating a ‘fire break’; or

- Spray on water to remove heat.

CBT examines problems in a similar way: the focus is on maintaining factors. Like a fire it’s not so important to know what started it, but we do need to know what is keeping it going. Therapists who use CBT are trained to pay particular attention to any sequences that appear to get stuck in a loop or jammed (where an action feeds back to cause more of the problem). There are many different ways that human problems can be maintained. Some of the most common maintaining factors that can keep our problems stuck include:

- Avoidance. Avoidance can be external (we might avoid people, places, or situations) or it can be internal (we might avoid thoughts, feelings, or body sensations). One difficulty caused by avoidance is the fact that it doesn’t give us an opportunity to find out how well we could have coped had we not avoided.

“Carl was so anxious about something catastrophic happening that he didn’t leave the house. He even avoided going near the front door.” - Biased memory. Memory bias means only recalling part of a story. People who are anxious find it easier to automatically remember threatening information. People who are depressed often have ‘overgeneral’ memory and find it hard to recall specific events. Memory bias means that we are making decisions based on only part of the story.

“When Simon was depressed he found it hard to remember how it had ever felt to be happy.” - Reinforcement. We are more likely to repeat actions that are followed by (are reinforced by) a good feeling – even if that behavior is not good for us in the long term.

“Nisha’s toddler cried for sweets when she saw them at the supermarket. Nisha bought some for her daughter to make the crying stop. The toddler was quick to notice the sweets next time they went shopping…” - Safety behaviors. Safety behaviors are things that we do to avoid what we believe could be a catastrophe. Like avoidance, one problem with using safety behaviors is that they can prevent us from learning whether the bad outcome would ever have happened.

“Bettie worried about embarrassing herself. Whenever she went to the cinema Bettie always sat in a seat next to the aisle in case she felt anxious and needed to make a quick getaway.” - Biased attention. Our attention is biased when we only notice part of a situation. One common problem is that if we only pay attention to our failures, and ignore our successes, we get a biased picture of ourselves.

“Julie had been hurt in the past. She was always on the lookout for ways she could be hurt again, and was very quick to notice when people (especially men) were acting in ways she found threatening. She was surprised that her friends didn’t see the dangers she saw.” - Biased thinking. There are many unhelpful thinking styles that mean we think about things in a ‘wonky’ or inaccurate way. Thinking in a biased way means that we are likely to reach biased conclusions. It would be a bit like a judge making a decision after only having listened to the evidence from the prosecution.

“Mary assumed that when people were looking at her, they were judging her harshly and would criticize her. In fact, people barely noticed her.” - Repetitive thinking. Rumination means going over and over problems and asking questions like “Why is my life always like this?”. Some ways of thinking don’t lead to the kinds of answers that will help us. Psychologists have found that “Why … ?” questions are less helpful than “How … ?” questions.

“Samantha went over and over her problems but never seemed to feel any better. She found it helpful to explore different ways of thinking with her therapist.” - Self-criticism. Self-criticism means telling ourselves off for things we think we have ‘done’ or ‘are’. In small doses a bit of self-criticism might be motivational (“Come on, you can do better!”) but it is more often the case that our self-criticism is said in a punishing rather than an encouraging tone. Some people’s inner critic can be oppressive.

“Lorraine’s inner critic would always put her down. It was quick to notice her faults but never offered any praise.”

How the pieces fit together: how problems persist

Psychologists have found that maintaining factors often join together in ‘typical’ ways to cause problems. In this section we will look at some common problems and explore the maintaining factors that keep them going.

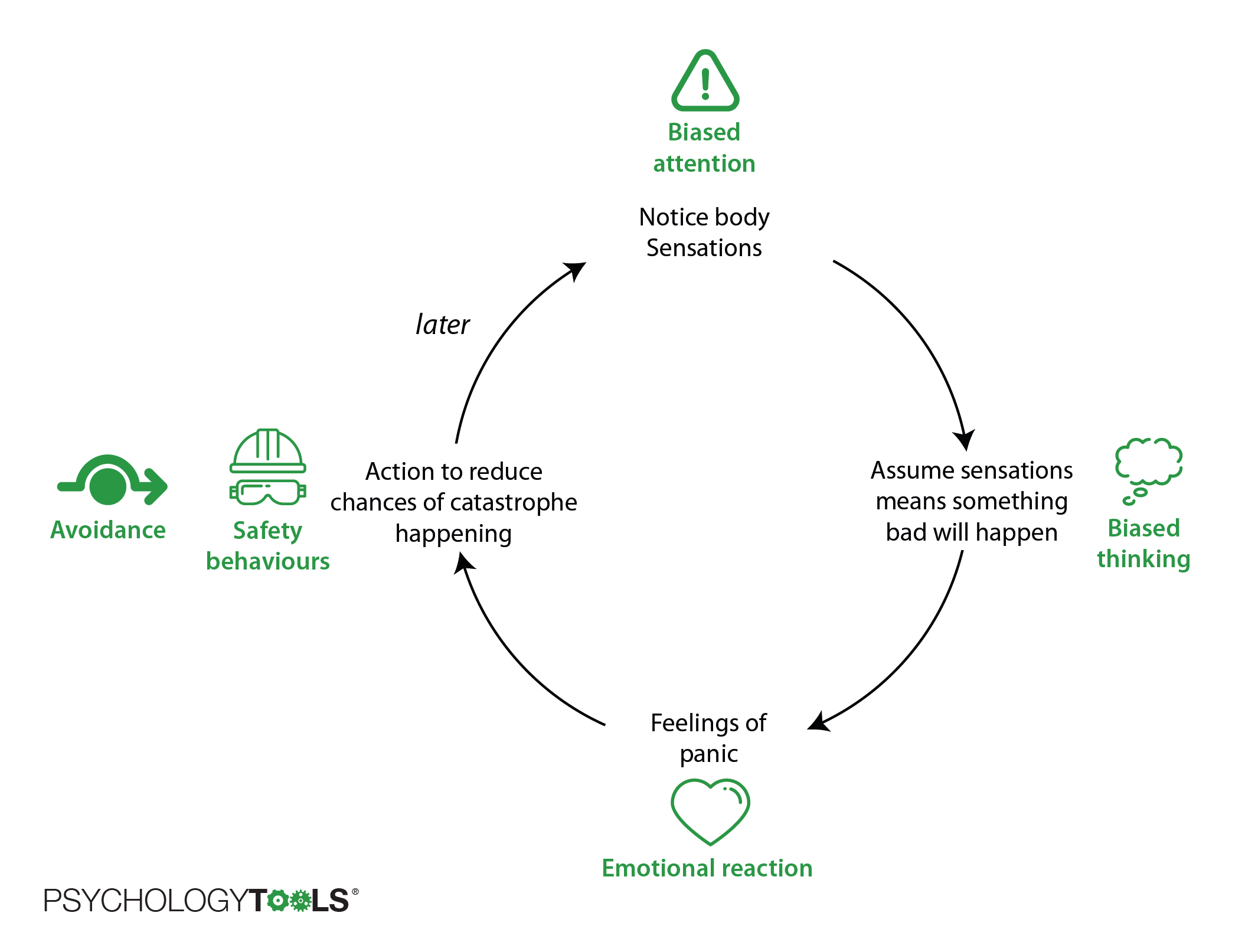

Anxiety

People who have panic attacks often notice ambiguous body sensations and assume that their presence means something terrible will happen. This way of thinking results in strong emotional reactions followed by understandable attempts to cope. The selective attention, biased thinking, and avoidance are important maintaining factors in panic. These are the areas that CBT treatment for panic will focus on.

Figure: The cycle of panic and the mechanisms that keep it going.

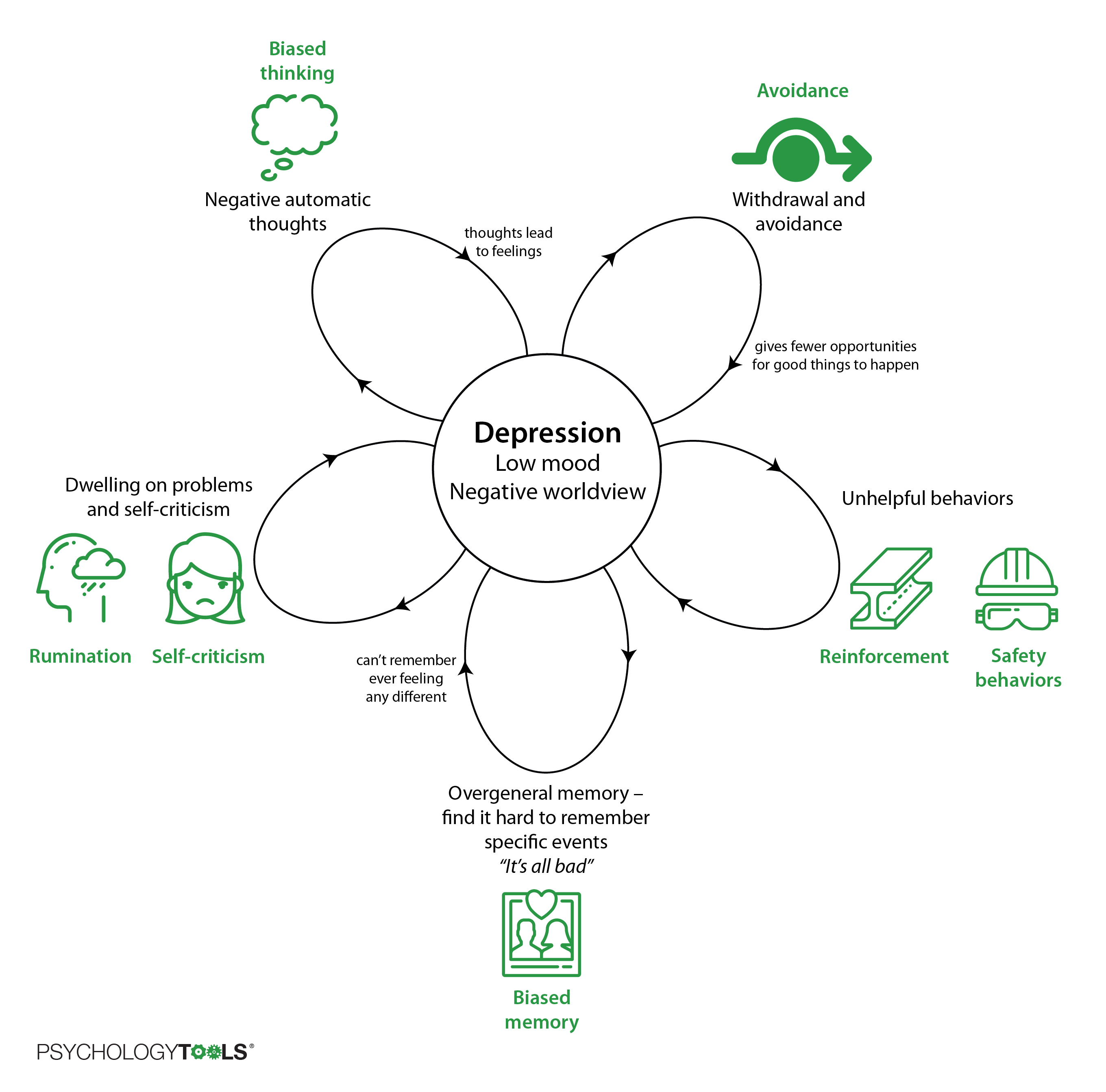

Depression

Similarly, for depression, CBT researchers have found that people with low mood experience changes in thinking and behavior and that these changes can keep the depression going. The diagram below shows how ‘depression mode’ can be maintained in some people.

Figure: One person’s cycle of depression with the mechanisms that keep it going.

Mixed problems

Many people struggle with more than one problem at once and not everyone’s problems fit neatly into models like those above. CBT is flexible though – using the same ‘building blocks’ it provides a framework for understanding problems so that and we can create our own models.

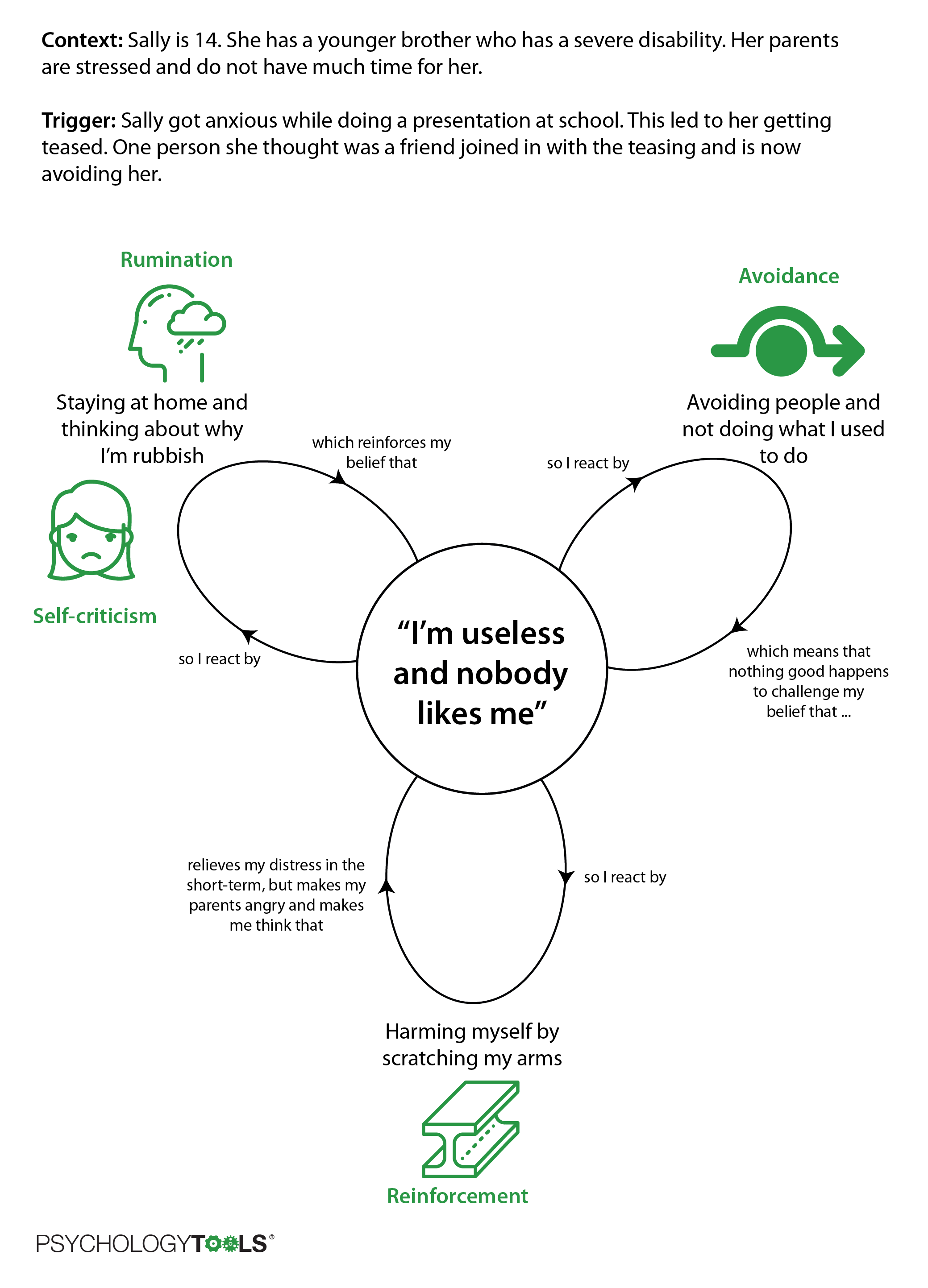

Figure: The building blocks of CBT can help us understand a huge variety of problems.

When Sally came to therapy she was really struggling. She and her therapist took the time to properly understand how she was feeling and identify the things that were maintaining her distress. Using this new understanding Sally, her therapist, and her parents came up with a plan to help her feel better.

Stage 3: Symptom monitoring in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Once a client and therapist have decided on which problem(s) to target, and have ideas about what might be maintaining the problem, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) places great emphasis on monitoring the problems and symptoms. In the same way that thoughts can be biased, our impressions about whether therapy is effective can be biased too. Therapists are especially prone to making assumptions about ‘how well’ therapy is going and can easily be mistaken. This bias can be overcome by regularly measuring symptoms and problems, and ‘checking in’ with clients about whether they think therapy is moving in the right direction. Evidence suggests that therapists who regularly monitor outcomes achieve better results for their clients.

Symptom monitoring can be as simple as counting how often something occurs – such as counting how often someone with panic experiences panic attacks, or counting how often someone with OCD performs one of their compulsions. CBT practitioners also use standardized questionnaires to measure symptom frequency or intensity. There are general measures which might measure anxiety or depression, to specific measures which explore what kinds of thoughts someone is experiencing.

David came to therapy because he was experiencing panic attacks. At the start of therapy his therapist asked him to keep a record of how many panic attacks he was experiencing each week. Then every week they would check in to see what was happening. By the time David completed treatment he was pleased not to have had any panic attacks in the previous three weeks.

Figure: Activity monitoring is one way of linking symptoms to behavior.

Stage 4: Techniques for change in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

Once we have assessed a problem, explored goals, and taken some educated guesses about why the problem is not getting better by itself it is time to take action. Sometimes the case conceptualization stage alone is enough to motivate change: people often feel helped by having spoken about a problem, may feel hopeful when they understand how it is operating, and often spontaneously make changes in their lives (this may explain why people often make ‘early gains’ in CBT treatment). Interventions in CBT are often focused on breaking maintenance cycles – interrupting the vicious cycles that keep problems going. We can separate these into CBT for:

- changing how you feel by learning something new,

- changing how you feel by changing what you think, and

- changing how you feel by changing what you do.

CBT Techniques for changing how you feel by learning something new (psychoeducation)

A crucial cognitive behavioral intervention is ensuring that clients have accurate information. According to the CBT model many problems stem from inaccurate interpretations about the meaning of a situation, trigger, or event. For example, a person with panic disorder may notice their heart racing and mistakenly conclude that they are having a heart attack (this would be a mistake: there are many good and safe reasons why our hearts can beat faster). Or a person with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) may assume that the frightening unwanted memories of their trauma mean that they are going mad (they’re not: it’s very common to have ‘flashbacks’ of traumatic events and there are good neurobiological reasons why this happens). In many cases giving people accurate information about why they are experiencing something is a fantastically powerful intervention.

As well as having conversations with their clients about psychological concepts and principles that they may not be aware of, another way that CBT therapists give their clients new information is with information handouts and CBT worksheets. Some of the most helpful CBT worksheets and information handouts for psychoeducation include:

- The fight or flight response worksheet. Our bodies are adapted (‘designed’) to help us survive danger and threats. One way in which they do this is by preparing the body to run away or fight – this is the fight or flight response. Some of the body changes can be uncomfortable or even frightening, especially if you don’t know why they are happening. The fight or flight response information handout describes the body sensations.

- Common intrusive thoughts worksheet. Thoughts, images, or urges which ‘pop’ involuntarily into our minds are called ‘intrusive’. We all have them, some of them are nice, and some of them might not be so nice. We might share the ones that are nice with other people – if you have the thought that your friend is looking healthy you might say “you look well today”. Conversely, we’re less likely to share the not-so-nice thoughts. This can mean that when we have not-so-nice thoughts we can assume that we are the only one having them: since we rarely hear other people talking about theirs. This assumption is a mistake though – intrusive thoughts are common, even the not-so-nice ones. This intrusive thoughts worksheet describes a variety of common intrusive thoughts which therapists can use as a game with their clients when exploring beliefs around intrusive thoughts.

- Ironic effects in mental control worksheet. A common-but-mistaken belief is that we are always in control of our own minds, and that our minds are controllable. It’s easy to see why we might make this mistake: we choose to think and do many things all day long. It’s just that we’re not always in complete control. For example, we all have intrusive thoughts that we might not have wanted, and we might feel feelings that we’re not keen on feeling. A psychologist called Daniel Wegner discovered a principle about how our minds operate which he called ‘ironic effects in mental control’. The idea is that our minds are not very good at not thinking of something. The more we try to push thoughts away the more they come back, a process call the rebound effect. Psychologists meet a lot of people who try this strategy. CBT therapists often conduct a small experiment in therapy where they ask clients not to think of a white bear and to pay attention to what happens. They might support this experiment with an understanding intrusive thoughts worksheet.

- Understanding how safety behaviors inadvertently maintain problems CBT worksheet. Safety behaviors are actions that we take with the intention of avoiding some form of catastrophic outcome. People who experience anxiety often employ safety behaviors as a way of feeling safer in the short-term. Unfortunately, safety behaviors often have the effect of maintaining anxiety because they can prevent learning about actual outcomes. CBT therapists might employ metaphors or CBT worksheets to explain what safety behaviors are, how they operate, and why they are unhelpful. The CBT safety behaviors worksheet is a concise and helpful tool for this purpose.

- Why schemas are resistant to change. People operate at different levels of cognition. At the top level we have automatic thoughts about here-and-now events, and at the bottom level we have core beliefs which are the product of our learning an experience. CBT therapists sometimes try to help their clients modify their core beliefs (schemas), an intervention which can require dedication and persistence because schemas are resistant to change. To help their clients understand why core beliefs might change more slowly than automatic thoughts it can be helpful to use a schema metaphors worksheet to illustrate how we think core beliefs operate.

- How abusers operate to obtain compliance CBT worksheet. Clients who have been physically, emotionally, or sexually abused by other people often feel intense shame about what happened to them, or about how they survived. They may regret having acted or failed to act in particular ways and are often extremely self-critical. A helpful approach when working with survivors of abuse is to take a compassionate external viewpoint in order to help clients to disengage from self-attack. One helpful discussion to have is to explore the abuse from the perpetrator’s point of view by asking “Assuming that your goal is to enjoy power and control over another person, what tactics might you employ to achieve your goal?”. The CBT worksheet ‘coercive methods for enforcing compliance’ can be a helpful way of exploring a client’s past experiences through the lens of an abusive perpetrator. Many clients report that it is a helpful way for them to understand their actions, and to blame themselves less for the ways in which they responded to abusive and manipulative behavior.

- Unhelpful thinking styles cognitive distortions CBT worksheet. We have discussed earlier in this article how people’s thinking can become biased. Common cognitive biases include overgeneralizing, catastrophizing, mind-reading, and labelling. The unhelpful thinking styles CBT worksheet is a great way of helping clients to understand common cognitive distortions.

CBT Techniques for changing how you feel by changing what you think (cognitive restructuring)

An important intervention in CBT is to help clients understand and change unhelpful patterns and types of thinking. One way in which practitioners of cognitive behavioral therapy help their clients to change how they think is by using CBT worksheets to scaffold their thought monitoring and thought modifying practice. There are a huge variety of CBT techniques and resources for helping people to change their thought processes. An essential first step in changing what we are thinking is to identify what is going through our minds – this is called ‘thought monitoring’. Cognitive behavioral therapists use a wide variety of CBT worksheets for thought monitoring. Once clients can reliably identify their negative automatic thoughts the next step is to examine the accuracy and helpfulness of these thoughts – a process called cognitive restructuring. Cognitive behavioral therapists use a wide variety of CBT worksheets for cognitive restructuring. An important type of CBT interventions to help clients consider alternative positions (change what they think) concerns conducting experiments. The classic approach is to conduct a behavioral experiment, of which there are many different variations. We will consider these in more detail in the next section.

- Simple Thought Record thought monitoring worksheet. A simple thought record worksheet is a great way of introducing clients to the process of monitoring their thoughts. It contains space to record the situation where the thought occurred, how it made them feel, and the thought or image that went through their mind at that time. It is helpful to remind clients that they should carry the thought monitoring worksheet with them so that they can make a note as soon as they practically can after they notice the thought. It is helpful to advise that the best time to complete a thought record worksheet is whenever you notice a sudden change in how you are feeling – a shift in your emotions is a good indicator that you have had a thought or appraised a situation in some way.

- CBT Thought Challenging Record worksheet. Challenging negative automatic thoughts (NATs) is an essential cognitive restructuring technique in cognitive behavioral therapy. Once clients have become adept at noticing and capturing their negative automatic thoughts, the next step is to examine how accurate they are and to learn to challenge unhelpful or inaccurate thoughts. A CBT thought record contains space to identify where and when a negative thought occurred, how it made you feel, and some details about the thought itself. The next steps encourage clients to identify all of the evidence that supports the truthfulness of the thought “What facts make you believe that thought is true?”. The next step requires clients to identify all of the evidence that might contradict the negative automatic thought – “What facts make you think this thought might not be 100% true all of the time?” – most clients find this step to be more difficult and may initially need more support. Once clients have identified as much contradictory evidence as they can the final step is to generate a more balanced thought which takes into account all of the evidence for and against the original negative automatic thought. This more balanced thought is often longer because it is more nuanced than the original NAT.

CBT Techniques for changing how you feel by changing what you do (or by learning new information)

The final but by no means least important class of CBT interventions concerns changing how you feel by changing what you do. To give you an idea of the importance of this class of interventions it is often said that “CBT is doing therapy not a talking therapy”. The interconnections in the CBT model mean that our actions / behaviors / responses have powerful feedback effects upon our thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and subsequent behaviors. Positive changes in behavior can result in virtuous circles and cascading improvements in cognition and mood. Many of the most powerful CBT interventions involve helping people to confront situations that they are afraid of, or to test the accuracy of some of their most deeply held beliefs by approaching situations without their normal defenses. Behavioral work in CBT often requires confidence and encouragement on the part of the therapist and courage on the part of the client, but behavioral techniques are some of the most powerful available.

- Behavioral experiment CBT worksheet. Behavioral experiments are probably the most important CBT tool for behavior change. They are an invaluable way for clients to learn new information for themselves. Behavioral experiments follow the maxim “show, don’t tell” or more precisely “allow the client to discover the truth for themselves”. The clinician’s stance is one of supportive curiosity. They take many different forms, but one of the most commonly used is the ‘hypothesis testing’ form of the behavioral experiment. A hypothesis testing behavioral experiment allows a client to test the evidence for one of their beliefs or assumptions. If a client expresses a belief “If I don’t hold on to my child’s stroller then I’ll have an attack of dizziness and collapse” their clinician can take a rating of how much the client believes this. The clinician approach is one of curiosity “Perhaps that’s true, how could we find out?”. The client is encouraged to identify their main hypothesis as well as an alternative “Maybe I won’t get the dizziness attacks anymore and I can walk unaided”. Then the client and therapist think of ways that these beliefs could be tested – experiments! The next stage is to conduct an experiment to find out what really happens, and often to repeat the experiments so as to obtain a fair result. The final stage is reflection upon the result “What have you learned?”.

- Exposure therapy CBT worksheet. Exposure therapy is one of the most effective treatments for anxiety. The essential message of exposure therapy is that ‘facing your fears’ is the best way of overcoming them. CBT worksheets for exposure therapy can be used to explain what exposure therapy is, help clients to structure fear hierarchies, and help them to record the outcomes of their exposure tasks.

- Behavioral activation CBT worksheet. Behavioral activation is an evidence-based treatment for depression. The idea is that by changing what we do we allow for different opportunities and contingencies. Cognitive behavioral therapists use a variety of CBT worksheets to assist their client with behavioral activation. Activity diaries are a useful way of understanding a client’s baseline level of activity. Activity planning diaries are a simple way of helping clients to schedule activities, and the activity diary with enjoyment and mastery ratings is a way of discovering which activities clients find the most rewarding.

- Problem-solving CBT worksheet. Sometimes we get stuck or feel stuck. It might seem as though our problems are not solvable and that our best approach is to avoid making a decision. Some clients may have a deficit in their problem-solving ability. The good news is that problem solving is an ability which can be taught and practiced. A classic problem solving approach is to (1) specify the problem that is troubling you (2) brainstorm possible solutions (feel free to go wild at this stage and identify any and all, no-matter how unrealistic they seem at this stage) then (3) identify advantages and disadvantages of each solution and (4) pick the best (or least-worst) solution and.

Summary

CBT is a powerful and flexible form of psychological therapy. There is a great deal of evidence that it is a helpful approach for a wide variety of problems including anxiety, depression, pain, and trauma. We know that it works when delivered face-to-face and can be effective as self-help. If you would like to access CBT for yourself then take a look at our finding a therapist page. If you would like to try CBT for yourself as self-help then read our Psychology Tools guides to thoughts, emotions, making sense of difficulties, and our guides to common psychological problems, and techniques for overcoming them.

What next?

If CBT sounds interesting to you, then the next step is to carry on working through the Psychology Tools Self-Help section. If you read each chapter and practice the exercises you will learn how to make CBT a useful part of your life. The next chapter is A Guide To Emotions.

References

[1] The Enchiridion of Epictetus

[2] Shakespeare, W. (1996). Hamlet. In T. J. Spencer (Ed.), The new Penguin Shakespeare. London, England: Penguin Books.

[3] Frankl, V. E. (1984). Man’s search for meaning: An introduction to logotherapy. New York: Simon & Schuster.

[4] Padesky, C. A., Mooney, K. A. (1990). Clinical tip: presenting the cognitive model to clients. International Cognitive Therapy Newsletter, 6, 13-14.

[5] Beck, J. S. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. New York: Guilford press.

[6] Beck, A. T. (1963). Thinking and depression: I. Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 9(4), 324-333.

[7] Newton, I. (1687) . Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica.

[8] Watts, S. E., Turnell, A., Kladnitski, N., Newby, J. M., & Andrews, G. (2015). Treatment-as-usual (TAU) is anything but usual: A meta-analysis of CBT versus TAU for anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 152-167.

[9] Hoffman, S. G., Asnaani, A., Vonk, I. J. J., Sawyer, A. T., & Fang, A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioural therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Therapy Research, 36, 427-440.