Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

Many of us will experience trauma at some point in our lives. With time, most people recover from their experiences without needing professional help. However, for a significant proportion of people the effects of trauma last for much longer, and they develop a condition called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It is thought that between 3 and 5 people out of every 100 will experience PTSD every year [1]. Fortunately, there are a range of excellent psychological therapies for PTSD.

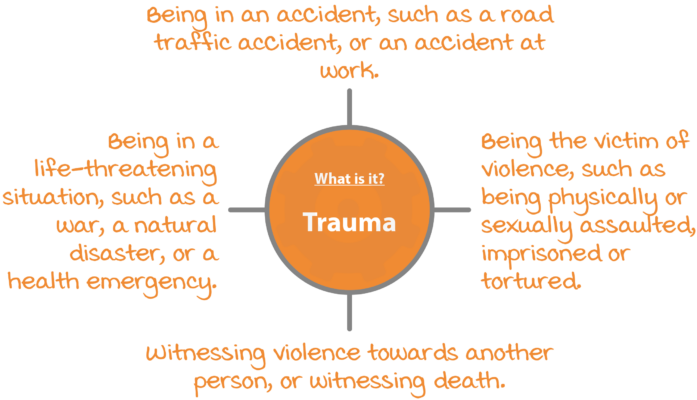

What is trauma?

A traumatic experience is one which is overwhelming, threatening, frightening, or out of our control. Common traumas include:

Some traumas are isolated one-off events that are unexpected and happen ‘out of the blue’. Other traumas are frightening in different ways: they are expected, anticipated, and dreaded. Some people’s jobs expose them to trauma, for example military or emergency service personnel often experience or witness distressing events. Children experience trauma too – and the effects can be even more profound and long-lasting if the people who were supposed to care for them were responsible for causing harm.

What is post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)?

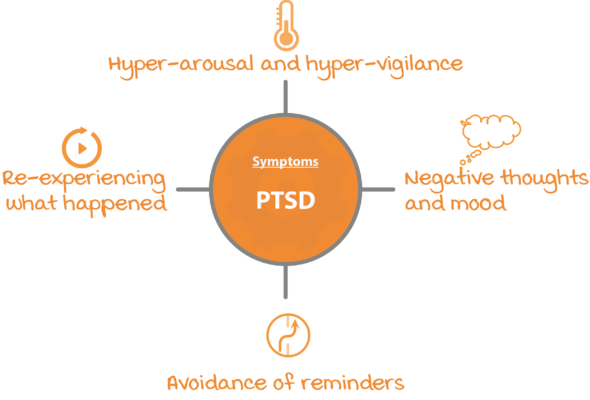

It is normal to be affected by traumatic experiences. If you have been through a trauma you might feel shocked, scared, guilty, ashamed, angry, vulnerable, or numb. With time most people recover from their experiences, or find a way to live with them, without needing professional help. However, for many people the effects of trauma last for much longer and may develop into post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Symptoms of PTSD can be split into groups [2].

Re-experiencing symptoms

Re-experiencing the trauma means that memories of the event play over and over in your mind. These memories can come back as ‘flashbacks’ during the day, or as nightmares at night. The memories can be re-experienced in any of your five senses – you might see images of what happened, or experience sounds, smells, tastes, or body sensations associated with the trauma. Emotions from the trauma can also be re-experienced and many trauma survivors say that it can feel as though the events are happening over and again. Re-experiencing symptoms include:

- Upsetting memories of the event intruding into your mind.

- Having nightmares about the event.

- Feeling physical reactions in your body when you are reminded of the event.

- Dissociation and feeling disconnected from the present moment.

Arousal symptoms

It is common to be ‘on edge’ or ‘on guard’ following a trauma. For people who have PTSD these feelings tend to persist for even longer than normal. You might find it very difficult to relax, or find that your sleep is affected. Arousal symptoms include:

- Always looking out for danger. Psychologists call this ‘hypervigilance’.

- Feeling ‘on edge’ or easily startled.

- Having difficulty falling or staying asleep.

- Having difficulty concentrating.

Avoidance symptoms

A normal human way of dealing with physical or emotional pain is to avoid it, or to distract ourselves. When you have PTSD you might try to avoid any people, places, or any other reminders of your trauma. You might try very hard to distract yourself in order to avoid thinking about what happened. Avoidance symptoms include:

- Avoiding reminders of the trauma.

- Trying not to talk or think about what happened.

- Feeling ‘numb’ or like you have no feelings.

Negative thoughts and mood

Trauma has a powerful effect on how we think. Many people with PTSD blame themselves for what happened, even when it was not their fault. Or you might replay parts of the trauma and think “what if …?” or “if only …”. Many people with PTSD also experience depression. Negative thoughts and mood about the trauma might include:

- Thinking negatively about yourself.

- Feeling guilty or ashamed about what happened.

- Feeling depressed or withdrawn.

- Feeling that no-one can be trusted.

What is Complex PTSD (CPTSD)?

Since PTSD was first identified in the 1970’s, research has shown that the kinds of symptoms that survivors of trauma have can look a bit different depending on:

- How much trauma a person has experienced.

- The type of trauma.

- When it happened in a person’s life.

People who have experienced a lot of trauma, have experienced trauma early in their lives, or have experienced trauma as a result of things that were done by their parents or caregivers often have extra symptoms in addition to PTSD:

- Severe problems in managing your emotions.

- Strong beliefs about yourself as diminished, defeated, or worthless.

- Difficulties in sustaining relationships and in feeling close to others.

When people experience these symptoms as well as PTSD, mental health professionals might label it Complex PTSD [3, 4]. You can think of it as ‘PTSD Plus’. Research indicates that many of the treatments that are effective for PTSD are also effective for people with Complex PTSD.

What is it like to have PTSD?

People with PTSD experience strong unwanted memories of their trauma, to the point where it can feel as though the trauma is happening again right now in the present moment. As a result, people with PTSD often feel on-edge and on the lookout for danger. Sushma describes what suffering from PTSD can be like. Some people find that reading about other people’s trauma can be upsetting, so feel free to skip this section until a time comes when you feel more able. Remember, though, that learning about trauma cannot harm you – it is the first step in overcoming PTSD.

Sushma’s fear, disgust, and shame

I grew up in a chaotic household. My father and brothers were violent and in and out of prison, and my mother was a mixture of critical and neglectful. When I was fourteen, a boy in my local park gave me alcohol and then raped me. I felt terrified during the attack and seemed to be frozen to the spot. I didn’t tell my parents what had happened because I knew they would blame me and I was worried about how they would react. I didn’t go to therapy until I was in my late twenties. When I did I was having daily flashbacks of the attack, and of the many of the other horrible things that had happened to me before and since. I would wake at night, terrified but unable to move, and I would sometimes wet the bed, which I was terribly ashamed of. When I got reminded of traumatic things I would sometimes dissociate so strongly that I would almost ‘forget’ where I was, and would feel like a terrified child again. I was convinced that I was a bad person – I thought “I’m rotten to the core” – and that I had deserved everything that had happened to me. I punished myself by not getting enough rest and was so self-critical. At the start of therapy, I was not very hopeful of recovering, and didn’t even think that I deserved to get help.

Do I have PTSD?

PTSD should only be diagnosed by a mental health professional or a doctor. However, answering the screening questions below can give you an idea of whether you might find it helpful to have a professional assessment.

| Have you ever experienced something unusually or especially frightening, horrible, or traumatic, such as being in a road traffic accident, or being physically or sexually assaulted? | Yes | No |

| If you answered yes, please answer the questions below about how you have felt in the past month. | ||

| Have you had nightmares about the event(s) or thought about the event(s) when you did not want to? | Yes | No |

| Have you tried hard not to think about the event(s) or gone out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of the event(s)? | Yes | No |

| Have you been constantly on guard, watchful, or easily startled? | Yes | No |

| Have you felt numb or detached from people, activities, or your surroundings? | Yes | No |

| Have you felt guilty or unable to stop blaming yourself or others for the event(s) or any problems the event(s) may have caused? | Yes | No |

If you answered “yes” to the first question, and to three or more of the other questions, you may be suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder. You might find it helpful to speak to your general practitioner, or a mental health professional about how you are feeling.

What causes PTSD?

The main cause of PTSD and Complex PTSD is being exposed to traumatic, life-threatening, or frightening events. Not everybody who experiences a trauma goes on to develop PTSD and it is not your fault if you suffer from it. Some of the things that make people more likely to develop PTSD after a traumatic experience include:

- How much social support you have.

- The way your brain processes memories of your trauma.

- Genetic and biological factors.

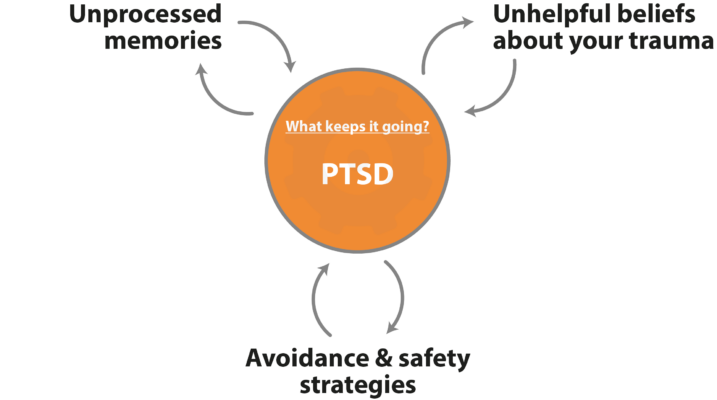

What keeps PTSD going?

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) is a popular evidence-based psychological therapy. It is always very interested in what keeps a problem going. This is because by working out what keeps a problem going, they can treat the problem by breaking the cycle. Psychologists Anke Ehlers and David Clark saw PTSD as a puzzle: why should people with PTSD feel a current sense of threat even though the terrible thing has already happened? They identified three big reasons [5]:

Treatments for PTSD

Psychological treatments for PTSD

Psychological treatments for PTSD which have strong research support include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) / Trauma-focused CBT [6, 7]

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) [6]

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) [7]

- Prolonged Exposure (PE) [7]

- Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) [8]

Although the mechanics of these therapies all differ slightly, they all contain some common ‘ingredients’:

- Exposure to memories.

- Work to change meanings.

- Reduction of unhelpful coping strategies.

Medical treatments for PTSD

The UK National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for post-traumatic stress disorder [10] found that there is evidence that a class of medications called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs: commonly known as ‘antidepressants’) and venlafaxine are effective in treating PTSD. However, these medications are less effective than psychological treatments and the NICE guidelines recommend that they should not be offered as a first-line treatment for PTSD. The NICE guidelines also found some evidence that antipsychotic medication may be helpful as an adjunct to psychological therapy in some cases.

References

- Kessler, R. C., Chiu, W. T., Demler, O., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(6), 617-627.

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5®). American Psychiatric Pub.

- Herman, J. L. (1992). Complex PTSD: A syndrome in survivors of prolonged and repeated trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 5(3), 377-391.

- Brewin, C. R., Cloitre, M., Hyland, P., Shevlin, M., Maercker, A., Bryant, R. A., … & Somasundaram, D. (2017). A review of current evidence regarding the ICD-11 proposals for diagnosing PTSD and complex PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 58, 1-15.

- Ehlers, A., & Clark, D. M. (2000). A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(4), 319-345.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2018). Post-traumatic stress disorder. Retrieved from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng116/resources/posttraumatic-stress-disorder-pdf-66141601777861

- Watkins, L. E., Sprang, K. R., & Rothbaum, B. (2018). Treating PTSD: a review of evidence-based psychotherapy interventions. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 12, 258.

- Robjant, K., & Fazel, M. (2010). The emerging evidence for narrative exposure therapy: A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(8), 1030-1039.

About this article

This article was written by Dr Matthew Whalley and Dr Hardeep Kaur, both clinical psychologists. It was last reviewed on 2021/12/08.