Professional version

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

A licensed copy of Shafran and colleagues (2002) cognitive behavioral model of clinical perfectionism.

Offers theory, guidance, and prompts for mental health professionals. Downloads are in Fillable PDF format where appropriate.

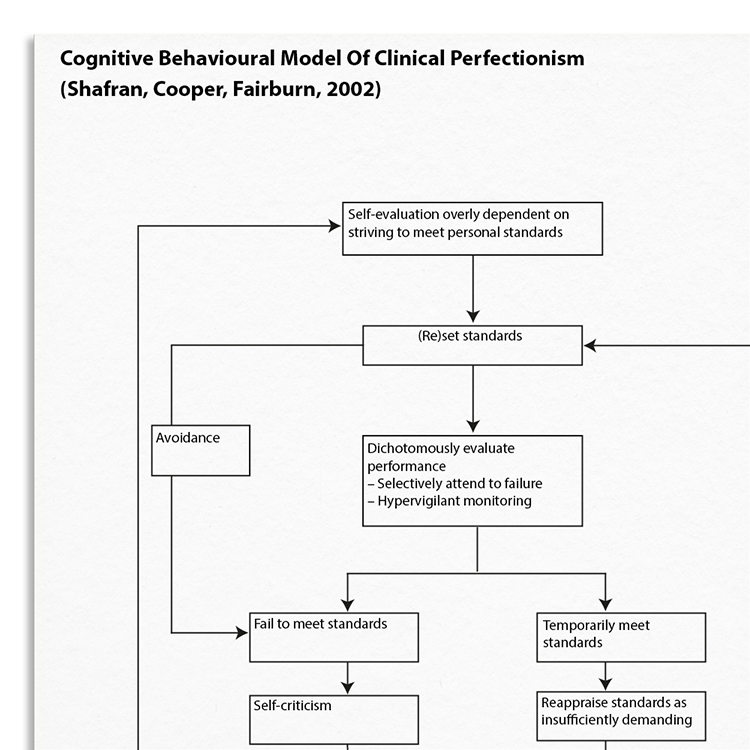

People with perfectionism pursue high standards in one or more areas of their life and base their self-worth on their ability to achieve these standards, even though this has negative consequences (Shafran, Egan, & Wade, 2010). Shafran, Cooper, & Fairburn's (2002) CBT model of perfectionism suggests that clinical perfectionism is maintained by an individual's biased evaluation of their progress towards achieving self-imposed high standards. Failure to meet these high standards is met with self-criticism and, if the standards are met, they may be re-evaluated as being insufficient. This information handout can be used to help conceptualize a client's perfectionism and enable exploration into its maintenance factors.

Understanding the underpinnings of clinical perfectionism is important for effective intervention. This resource helps clinicians to:

Perfectionism associated with shape, weight, and eating.

Perfectionism associated with rituals and compulsions.

Perfectionistic standards associated with worry and anxiety.

Understand more about the cognitive behavioral model of clinical perfectionism.

Use the model as a template to organize your case formulations.

Use your knowledge of the model to explain maintenance processes to clients.

Engage clients in discussions about their beliefs and behaviors.

Customize interventions based on individual maintenance mechanisms.

Use in supervision to discuss case conceptualizations and treatment plans.

People with perfectionism pursue high standards in one or more areas of their life and base their self-worth on their ability to achieve these standards, even though this has negative consequences (Shafran, Egan, & Wade, 2010). Perfectionism can arise in domains including: work, appearance, bodily hygiene, social and romantic relationships, eating habits, health, time management, hobbies and leisure activities, sports, orderliness, and several others (Stoeber, J., & Stoeber, F., 2009). Core symptoms of perfectionism include, pursuing standards that are highly demanding, fear of failure, intense self-criticism when standards are unmet, and counterproductive performance-related behaviors (e.g., excessive checking, comparison-making, or reassurance-seeking).

The high levels of perfectionism observed amongst individuals with eating disorders led Shafran, Cooper & Fairburn (2002) to develop the first cognitive behavioral model of perfectionism. The model was later revised to explain more explicitly the role of performance-checking behaviors – such as reassurance-seeking – in perfectionism (Shafran, Egan, & Wade, 2010). Some of the key components of the earlier model include self-evaluation which is overly dependent on striving to meet standards, setting standards that are excessive, evaluating performance in a dichotomous manner.

Just enter your name and email address, and we'll send you Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Clinical Perfectionism (Shafran, Cooper, Fairburn, 2002) (English US) straight to your inbox. You'll also receive occasional product update emails wth evidence-based tools, clinical resources, and the latest psychological research.

Working...

This site uses strictly necessary cookies to function. We do not use cookies for analytics, marketing, or tracking purposes. By clicking “OK”, you agree to the use of these essential cookies. Read our Cookie Policy