Safety-Seeking Behaviors / Safety Behaviors

Safety-seeking behaviors are behaviors that are carried out (either overtly or covertly) in specific situations in order to prevent feared outcomes (Salkovskis, 1991). Many safety-seeking behaviors are helpful and adaptive when the concern is real and the behavior can genuinely reduce the danger, such as checking the temperature of the water before getting in the bath or looking both ways before crossing the road. However, when safety-seeking behaviors concern perceived threats rather than actual dangers they are either unnecessary or can serve to exacerbate and maintain the anxiety.

The identification of safety-seeking behaviors has helped to explain the paradoxical observation that people with anxiety disorders have repeated experiences indicating that their fear is not warranted, yet fail to learn from their experiences (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell, & Shafran, 2004; Clark, 1999). Salkovskis (1991) states:

“In order to account for the failure of anxious patients to take advantage of naturally occurring disconfirmations, the cognitive hypothesis postulates a functional and internally logical link between cognition and behaviour … That is, a person panicking because he believes that a catastrophe is imminent will do anything he believes he can do to prevent the catastrophe. The person afraid of fainting sits, the person afraid of having a heart attack refrains from exercising, and so on. By doing so, the patient not only experiences immediate relief, but also unwittingly ‘protects’ his or her belief of the potential for disaster associated with particular sensations. Each panic attack, rather than being experienced as a disconfirmation, becomes another example of nearly being overtaken by disaster; ‘I have been close to fainting so many times: I have to be careful, or one of these times I won’t be able to catch it.’ This means that the apparent failure of panic patients to take advantage of natural disconfirmations may be because the non-occurrence of feared catastrophes, when associated with safety seeking behaviour, does not constitute an actual disconfirmation, and may sometimes be perceived as confirmation of a ‘near miss.’ ”

Showing 1 to 50 of 125 results

Assertive Communication – 'I-Messages' Or 'I-Statements'

Assertive Communication – 'I-Messages' Or 'I-Statements'

Understanding Bipolar Disorder

Understanding Bipolar Disorder

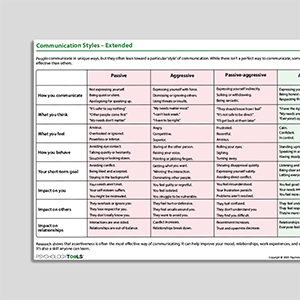

Communication Styles – Extended

[Free Guide] Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

[Free Guide] Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

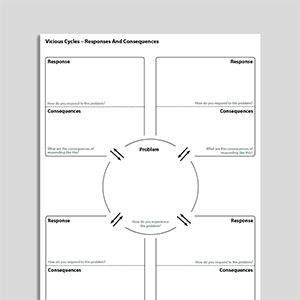

Vicious Cycle - Responses And Consequences

Vicious Cycle - Responses And Consequences

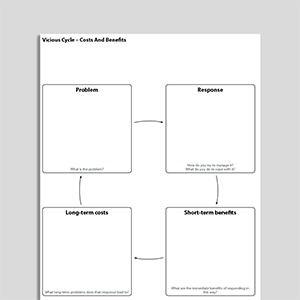

Vicious Cycle - Costs And Benefits

Vicious Cycle - Costs And Benefits

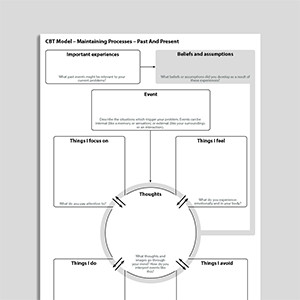

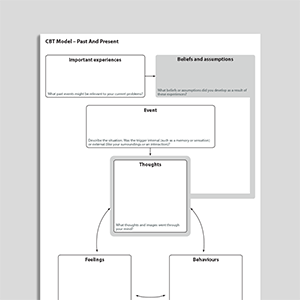

CBT Model – Maintaining Processes – Past And Present

CBT Model – Maintaining Processes – Past And Present

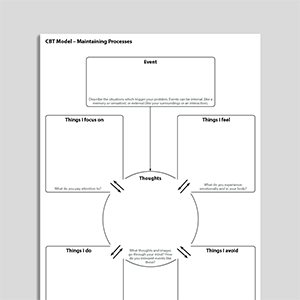

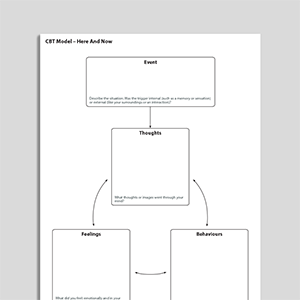

CBT Model – Maintaining Processes

CBT Model – Maintaining Processes

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Client Workbook

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Client Workbook

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Unified Protocol for Transdiagnostic Treatment of Emotional Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Exposures For Fear Of Vomiting

Exposures For Fear Of Vomiting

Exposures For Fear Of Uncertainty

Exposures For Fear Of Uncertainty

Exposures For Fear Of Flying

Exposures For Fear Of Flying

Exposures For Fear Of Heights

Exposures For Fear Of Heights

Exposures For Fear Of Losing Control Of Your Mind

Exposures For Fear Of Losing Control Of Your Mind

Exposures For Fear Of Illness

Exposures For Fear Of Illness

Exposures For Fear Of Death

Exposures For Fear Of Death

Exposures For Fear Of Breathlessness

Exposures For Fear Of Breathlessness

Exposures For Fear Of Body Sensations

Exposures For Fear Of Body Sensations

Exposures For Fear Of Appearing Anxious

Exposures For Fear Of Appearing Anxious

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

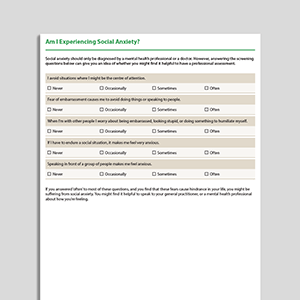

Am I Experiencing Social Anxiety?

Am I Experiencing Social Anxiety?

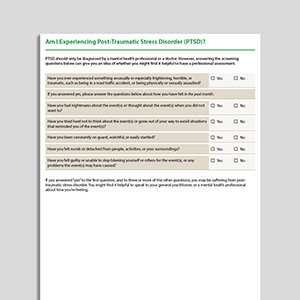

Am I Experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

Am I Experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

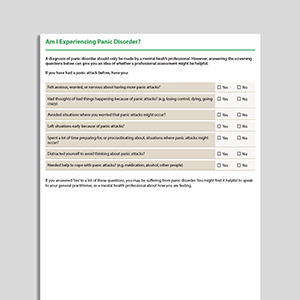

Am I Experiencing Panic Disorder?

Am I Experiencing Panic Disorder?

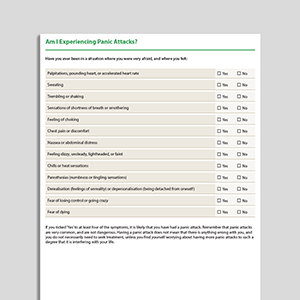

Am I Experiencing Panic Attacks?

Am I Experiencing Panic Attacks?

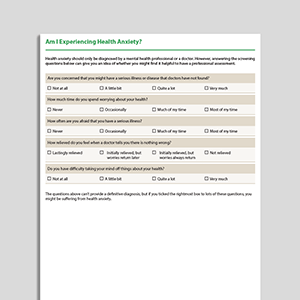

Am I Experiencing Health Anxiety?

Am I Experiencing Health Anxiety?

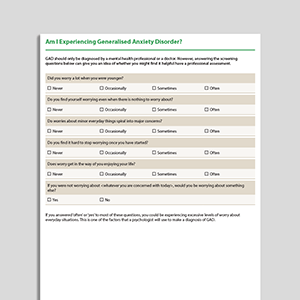

Am I Experiencing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

Am I Experiencing Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD)?

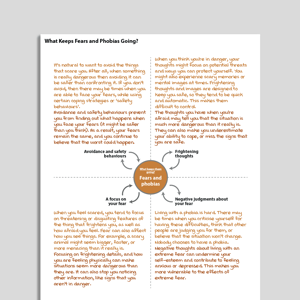

What Keeps Fears And Phobias Going?

What Keeps Fears And Phobias Going?

Understanding Fears And Phobias

Understanding Fears And Phobias

Facing Your Fears And Phobias

Facing Your Fears And Phobias

Mastery Of Your Anxiety And Worry (Second Edition): Workbook

Mastery Of Your Anxiety And Worry (Second Edition): Workbook

Mastery Of Your Anxiety And Worry (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Mastery Of Your Anxiety And Worry (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Managing Social Anxiety (Third Edition): Workbook

Managing Social Anxiety (Third Edition): Workbook

Managing Social Anxiety (Third Edition): Therapist Guide

Managing Social Anxiety (Third Edition): Therapist Guide

Reclaiming Your Life From A Traumatic Experience (Second Edition): Workbook

Reclaiming Your Life From A Traumatic Experience (Second Edition): Workbook

Prolonged Exposure Therapy For PTSD (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Prolonged Exposure Therapy For PTSD (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Treating Your OCD With Exposure And Response (Ritual) Prevention (Second Edition): Workbook

Treating Your OCD With Exposure And Response (Ritual) Prevention (Second Edition): Workbook

Exposure And Response (Ritual) Prevention For Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Exposure And Response (Ritual) Prevention For Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Childhood OCD: It's Only a False Alarm: Workbook

Cognitive Behavioral Treatment of Childhood OCD: It's Only a False Alarm: Workbook

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Recommended Reading

- Helbig‐Lang, S., & Petermann, F. (2010). Tolerate or eliminate? A systematic review on the effects of safety behavior across anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(3), 218-233.

- Rachman, S., Radomsky, A. S., & Shafran, R. (2008). Safety behaviour: A reconsideration. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 46(2), 163-173 archive.org

- Salkovskis, P. M. (1991). The importance of behaviour in the maintenance of anxiety and panic: a cognitive account. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19, 6-19

- Salkovskis, P. M., Clark, D. M., Hackmann, A., Wells, A., Gelder, M. G. (1999). An experimental investigation of the role of safety-seeking behaviours in the maintenance of panic disorder with agoraphobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37, 559-574 archive.org

- Thwaites, R., Freeston, M. H. (2005). Safety-seeking behaviours: Fact or function? How can we clinically differentiate between safety-seeking behaviours and adaptive coping strategies across anxiety disorders? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33, 177-188

What Are Safety Behaviors?

Blakey et al. (2019) review safety behaviors from an inhibitory learning standpoint and argue that safety behaviors interfere with safety learning in three ways:they could prevent the violation of expectancies by attenuating the discrepancy between what the patient predicts will occur during an exposure task (i.e., catastrophe) and what actually occurs (i.e., no catastrophe);

safety behaviors might obstruct the generalization of safety-based associations by restricting safety learning to specific contexts;

they could impede the development of distress tolerance by obstructing patients from learning that they can persist in challenging tasks despite elevate levels of distress.

| Function | |||

| Preventive | Restorative | ||

| Strategy | Behavioral | Situational avoidanceRelying on safety signalsSubtle avoidanceCompulsive behavior carried out to prevent an increase in anxiety | EscapeUse of safety signalsCompulsive behavior carried out to decrease anxietyReassurance seeking |

| Cognitive | Preparation | Distraction/focusingNeutralizingThought suppression | |

Disorders That May Be Maintained by Safety-Seeking Behaviors

Harvey et al. (2004) propose that safety-seeking behavior is present in:panic disorder with or without agoraphobia

specific phobia

social phobia

post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)

body dysmorphic disorder

eating disorders

insomnia

psychosis

Helpful Questions for Assessing Safety-Seeking Behaviors

Some helpful questions for assessing safety-seeking behaviors include:How do you respond when you feel threatened?

In situations where you feel anxious but can’t or don’t escape, what do you do to cope?

What are the short-term effects of coping in that way?

What would happen if you stopped using that safety behavior?

Treatment Approaches That Target Safety-Seeking Behaviors

The traditional approach to the treatment of anxiety is to expose the patient to the feared situation or stimulus with encouragement to drop the use of safety-seeking behaviors. Recent research has questioned whether the judicious use of safety behaviors might make exposure tasks more acceptable to patients, and might facilitate approach behaviors. Current evidence is mixed, with the authors of a 2019 trial concluding:“… therapists may not need to be concerned if their patient is unwilling to immediately eliminate their safety behavior(s) as long as the patient explicitly tests their fear-based negative expectancies through direct and sustained confrontation with feared situations/stimuli and also understands they should eliminate their use of safety behaviors as soon as they are willing” (Blakey et al., 2019).

References

Blakey, S. M., Abramowitz, J. S., Buchholz, J. L., Jessup, S. C., Jacoby, R. J., Reuman, L., & Pentel, K. Z. (2019). A randomized controlled trial of the judicious use of safety behaviors during exposure therapy. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 112, 28–35.

Clark, D. M. (1999). Anxiety disorders: Why they persist and how to treat them. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 37(1), S5.

Harvey, A. G., Watkins, E., Mansell, W., & Shafran, R. (2004). Cognitive behavioural processes across psychological disorders: A transdiagnostic approach to research and treatment. New York: Oxford University Press.

Helbig-Lang, S., & Petermann, F. (2010). Tolerate or eliminate? A systematic review on the effects of safety behavior across anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 17(3), 218–233.

Salkovskis, P. M. (1991). The importance of behaviourin the maintenance of anxiety and panic: A cognitive account. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 19(1), 6–19.

![[Free Guide] Understanding Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)](https://assets-media.psychologytools.com/29108/conversions/*free_understanding-ptsd_en-gb_Guides_Cover-preview.png)