Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring is a technique which cognitive behavioral therapists almost always teach their clients. It is a form of data-gathering in which clients are asked to systematically observe and record specific targets such as their own thoughts, emotions, body feelings, and behaviors. For example, a depressed client might be asked to record information about situations where their mood felt particularly low, a client recovering from an addiction problem might record what they were doing and thinking just prior to using substances, or a client suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder might complete a diary to record details of their trauma flashbacks.One aim of CBT is to help people to understand how what they think and do affects the way they feel. The process of self-monitoring can help clients better appreciate the links between situations, thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and their responses. Self-monitoring can provide a simple means to track client progress (e.g. measuring the frequency and intensity of intrusive thoughts over the course of therapy) as well as readiness for different stages of a treatment intervention (e.g. the introduction of cognitive restructuring or behavioral experiments).Although self-monitoring is conceptually fairly simple, it is often challenging for clients to conduct effectively (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999). To support clients with self-monitoring, we have outlined below a number of best practices that can be followed.

Showing 1 to 50 of 65 results

Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach (Second Edition): Workbook

Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach (Second Edition): Workbook

Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Trichotillomania: An ACT-Enhanced Behavior Therapy Approach (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Effective Weight Loss: An Acceptance-Based Behavioral Approach: Workbook

Effective Weight Loss: An Acceptance-Based Behavioral Approach: Clinician Guide

Effective Weight Loss: An Acceptance-Based Behavioral Approach: Clinician Guide

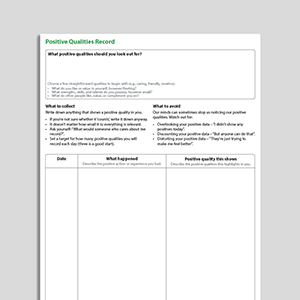

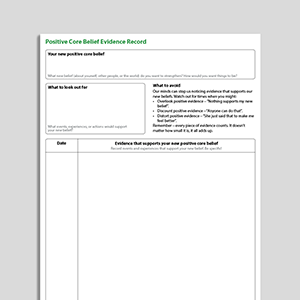

Positive Core Belief Evidence Record

Positive Core Belief Evidence Record

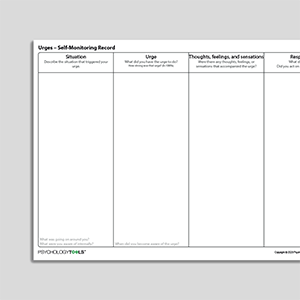

Urges – Self-Monitoring Record

Urges – Self-Monitoring Record

Permissive Thinking – Self-Monitoring Record

Permissive Thinking – Self-Monitoring Record

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

Audio Collection: Psychology Tools For Overcoming PTSD

Anxiety Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Anxiety Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Anger Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Anger Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

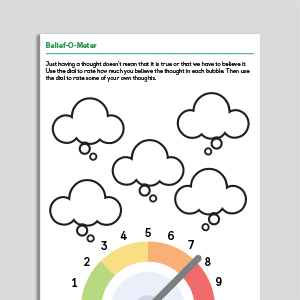

Evaluating Unhelpful Automatic Thoughts

Evaluating Unhelpful Automatic Thoughts

Perfectionism Self-Monitoring Record

Perfectionism Self-Monitoring Record

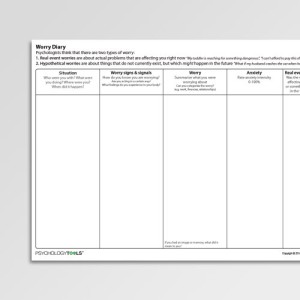

Worry – Self-Monitoring Record

Worry – Self-Monitoring Record

Self-Monitoring Record (Universal)

Self-Monitoring Record (Universal)

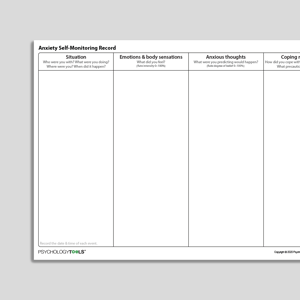

Anxiety - Self-Monitoring Record

Anxiety - Self-Monitoring Record

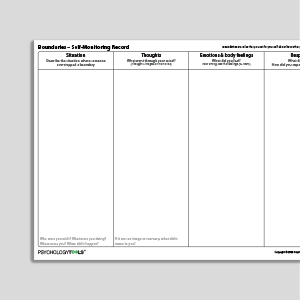

Boundaries - Self-Monitoring Record

Boundaries - Self-Monitoring Record

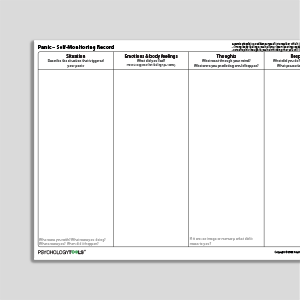

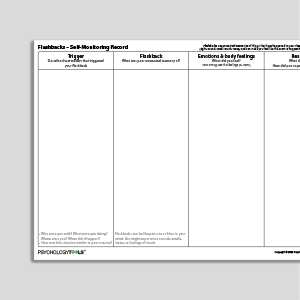

Flashbacks - Self-Monitoring Record

Flashbacks - Self-Monitoring Record

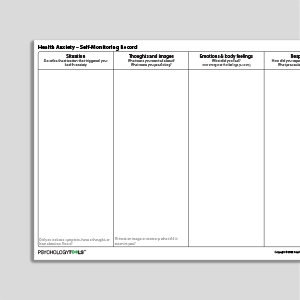

Health Anxiety - Self-Monitoring Record

Health Anxiety - Self-Monitoring Record

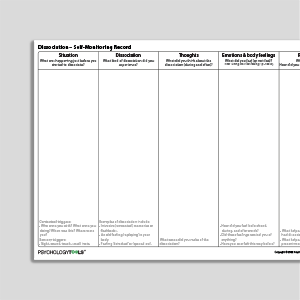

Dissociation - Self-Monitoring Record

Dissociation - Self-Monitoring Record

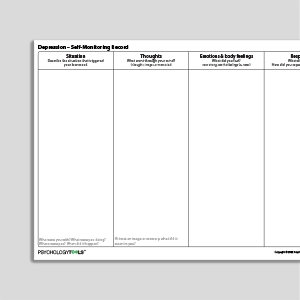

Depression - Self-Monitoring Record

Depression - Self-Monitoring Record

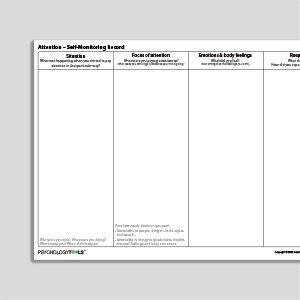

Attention - Self-Monitoring Record

Attention - Self-Monitoring Record

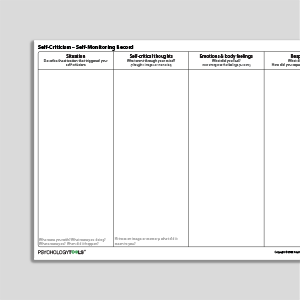

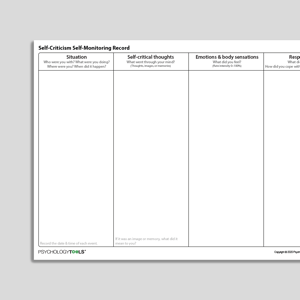

Self-Criticism - Self-Monitoring Record

Self-Criticism - Self-Monitoring Record

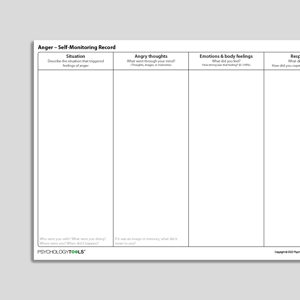

Anger - Self-Monitoring Record

Anger - Self-Monitoring Record

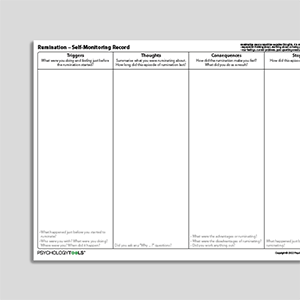

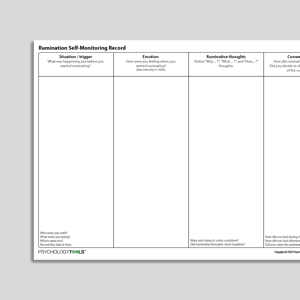

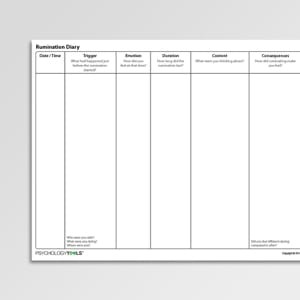

Rumination - Self-Monitoring Record

Rumination - Self-Monitoring Record

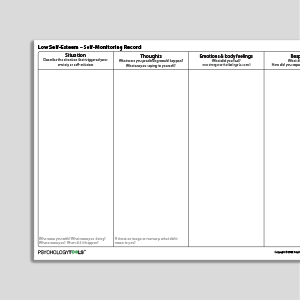

Low Self-Esteem - Self-Monitoring Record

Low Self-Esteem - Self-Monitoring Record

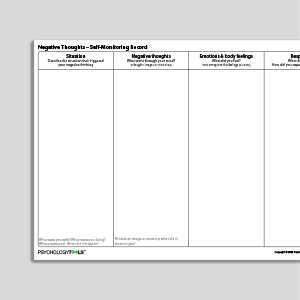

Negative Thoughts - Self-Monitoring Record

Negative Thoughts - Self-Monitoring Record

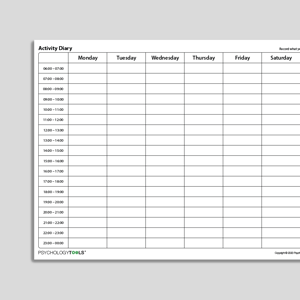

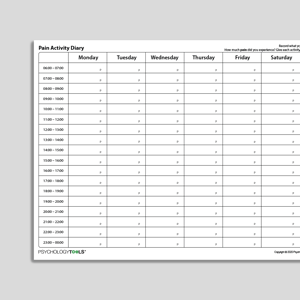

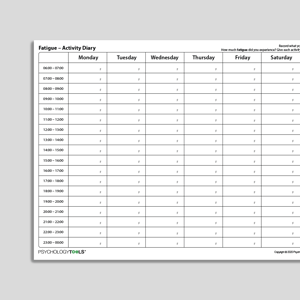

Activity Diary (Hourly Time Intervals)

Activity Diary (Hourly Time Intervals)

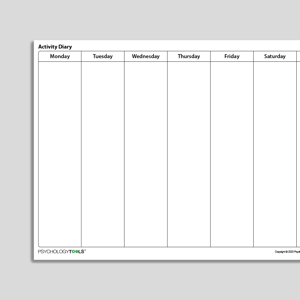

Activity Diary (No Time Intervals)

Activity Diary (No Time Intervals)

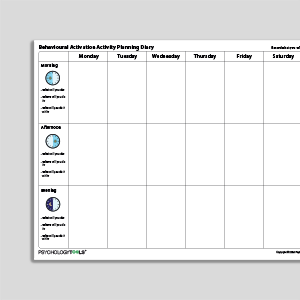

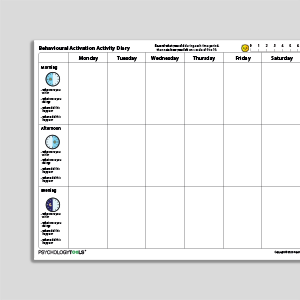

Behavioral Activation Activity Planning Diary

Behavioral Activation Activity Planning Diary

Behavioral Activation Activity Diary

Behavioral Activation Activity Diary

Challenging Your Negative Thinking (Archived)

Challenging Your Negative Thinking (Archived)

Rumination Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Rumination Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

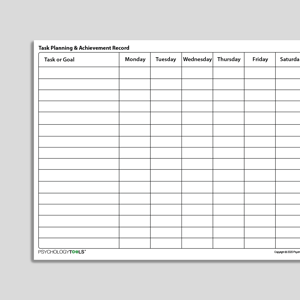

Task Planning And Achievement Record

Task Planning And Achievement Record

Self-Criticism Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

Self-Criticism Self-Monitoring Record (Archived)

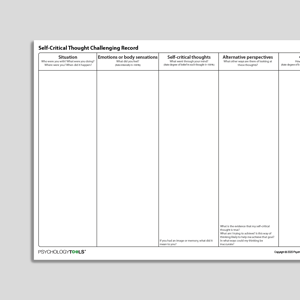

Self Critical Thought Challenging Record

Self Critical Thought Challenging Record

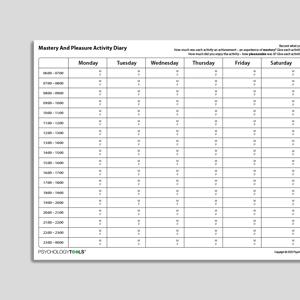

Mastery And Pleasure Activity Diary

Mastery And Pleasure Activity Diary

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Information Handouts

- Instructions for self monitoring (eating disorders) | CREDO

Worksheets

- Blank Monitoring Record | CREDO

What is self-monitoring in therapy?

Self-monitoring is a practice in which clients are asked to systematically observe and record specific targets such as thoughts, body feelings, emotions, and behaviors. It is part of a wider practice of empiricism and measurement that is integral to CBT (Persons, 2008), and it functions as both an assessment method and an intervention (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999; Proudfoot & Nicholas, 2010). Self-monitoring is comprised of two parts – discrimination and recording (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999).During discrimination, the client is trained to bring their awareness to target phenomena by identifying and noticing when they occur. For many clients, bringing attention and awareness to specific thoughts, feelings or emotions will be novel and difficult, but improving clients’ awareness of their symptoms and behavior is a critical component of CBT.Recording consists of documenting occurrences (usually through a written record). Creating a record makes discrimination an explicit and conscious process that can be reviewed and analyzed. It also means that – through documentation of specific events – additional detail or context can be included and analyzed, improving the client’s understanding of their symptoms, as well as the sequence and process by which they occur. Discrimination and recording are skills that need to be learned and honed. Clients are likely to need support and training to complete self-monitoring records accurately.Self-monitoring is ubiquitous across CBT, with “self-monitoring procedures… described and recommended within most empirically supported treatments” (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999). Therapists and clients may not always label it as self-monitoring, and may instead refer to the use of diaries, logs, records, schedules, or symptom monitoring. Commonly used examples are activity diaries for behavioral activation, logs of eating behaviors for the treatment of eating disorders, and thought records for capturing negative automatic thoughts.Why practice self-monitoring in CBT?

“Self-monitoring puts clients in charge of empirically examining their beliefs and behavior.” (Cohen et al, 2013)CBT is an open (non-mysterious) therapy in which the client is an active participant, and where the goal is to help clients to develop skills to manage or overcome their difficulties. Self-monitoring is a straightforward way to introduce clients to the concept of active participation in therapy, and it supports clients’ engagement and motivation by fostering a sense of self-control and autonomy (Bornstein, Hamilton & Bornstein, 1986; Proudfoot & Nicholas, 2010). By completing self-monitoring records away from therapy sessions, clients gain additional feedback that serves to reinforce and consolidate the work completed in sessions (Bornstein, Hamilton & Bornstein, 1986).Self-monitoring helps clients to develop a critical awareness of their difficulties, which prepares them for change: “awareness is a logical first step of the change process” (Persons, 2008). For example, self-monitoring the frequency of angry outbursts can help clients to see the true scale of the problem (that they shout at their partner nearly every day, not once every fortnight as they initially reported). Self-monitoring the time taken to complete compulsive rituals can help a client with OCD to see how much time they lose each day, and can help to build motivation to engage in therapy. As skills in discrimination improve, self-monitoring can be refocused to help clients better understand the links between situations, thoughts, emotions, body sensations, and their responses.An additional benefit of self-monitoring is that, in some circumstances, it has been shown to have a modest but beneficial treatment effect – so called ‘reactive’ effects (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999; Proudfoot & Nicholas, 2010). The act of self-monitoring has been shown to increase the frequency of positive behaviors and decrease the frequency of negative behaviors (e.g. for eating disorders or substance misuse; Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999). Because of this, self-monitoring can make an ‘adjunctive contribution’ to interventions (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999).

When should self-monitoring be practiced in therapy?

Self-monitoring is often taught early in therapy, during the assessment stage. It can be particularly useful when the target phenomenon is covert and cannot be observed by anyone but the client themself (Cohen et al, 2013), for example, negative automatic thoughts, body sensations or self-harm.Since self-monitoring is both a form of assessment and an intervention (Korotitsch & Nelson-Gray, 1999; Proudfoot & Nicholas, 2010), the format and nature of self-monitoring is likely to change during therapy. Self-monitoring may initially focus more on capturing data to help the client and therapist identify and prioritize problems. Subsequent data might be used to inform a client’s formulation – for example, monitoring triggers and environmental factors to identify causal relationships to the problem. Once an intervention plan has been developed, self-monitoring can be used to track the plan’s implementation away from therapy sessions, such as monitoring the frequency and success with which a new adaptative coping strategy is used (Cohen et al, 2013). Finally, self-monitoring might be used throughout therapy as a method of measuring the effectiveness of treatment as a whole and whether therapy goals have been met.How is self-monitoring conducted?

Events can be ‘monitored’ retrospectively, with the client and therapist working together in-session to review the client’s memory for an event, and exploring their thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. The downside to this approach is that retrospective records are affected by recall biases, so salient elements are particularly likely to be recalled (such as body feelings), whereas other details are likely to be lost or recalled inaccurately (such as contextual triggers or preceding thoughts; Proudfoot & Nicholas, 2010). The advantage self-monitoring is that the client can record information close to (or at the time of) an event and this often results in a richer, more complete and accurate account (Bornstein, Hamilton & Bornstein, 1986).What are common targets of self-monitoring in CBT?

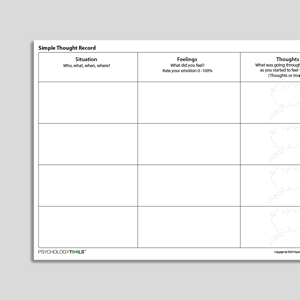

Targets for self-monitoring are idiosyncratic, depending upon the client’s presentation. Target domains include:Events: e.g. monitoring events in which a client feels a certain way.

Emotions: e.g. monitoring situations in which particular emotions are experienced.

Thoughts: e.g. monitoring the occurrence, frequency, and content of negative thoughts.

Memories: e.g. monitoring the occurrence, frequency, and content of unwanted memories.

Body sensations: e.g. monitoring the occurrence, frequency, triggers, context and consequences of physiological feelings that concern the client.

Attention: e.g. monitoring situations where a client becomes particularly self-focused, or especially threat-focused.

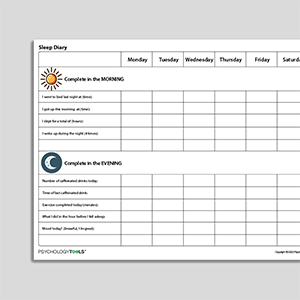

Activity: e.g. monitoring daily levels of activity in depression, or monitoring the relationship between activity, enjoyment, and mastery.

Behavior: e.g. monitoring behaviors such as avoidance, self-harm, safety behaviors, appeasement, bingeing and purging.

How to train clients in self-monitoring in CBT

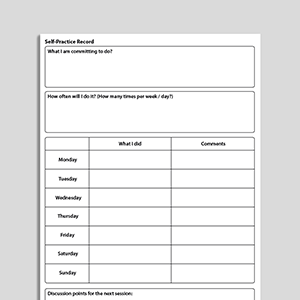

Self-monitoring is a skill that develops with time and training, so clients may need support to complete self-monitoring records accurately. Elements of effective training include:Select a relevant target for monitoring – will data about this influence clinical decision making?

Ensure the target is specific, clearly defined and agreed upon – does the client understand what they are monitoring and why?

Provide clear instructions – does the client understand how to complete self-monitoring? Can they refer back to instructions without the therapist?

Offer concrete support for recording – how will recording be completed? Does the client have the necessary resources and materials?

Provide modeling and training in how to record – has the client practiced recording? Has the therapist observed the client practicing?

Use the monitoring data – subsequent sessions should always review and draw upon prior self-monitoring data the client has recorded.

References

Bornstein, P.H., Hamilton, S.B. & Bornstein, M.T. (1986). Self-monitoring procedures. In A.R. Ciminero, K.S. Calhoun, & H.E. Adams (Eds) Handbook of behavioral assessment (2nd ed). New York: Wiley.

Cohen, J.S., Edmunds, J.M., Brodman, D.M., Benjamin, C.L., Kendall, P.C. (2013). Using self-monitoring: implementation of collaborative empiricism in cognitive-behavioral therapy. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(4), 419-428.

Kennerley, H., Kirk, J., & Westbrook, D. (2017). An Introduction to Cognitive Behaviour Therapy: Skills & Applications. 3rd Edition. Sage, London.

Korotitsch, W. J., & Nelson-Gray, R. O. (1999). An overview of self-monitoring research in assessment and treatment. Psychological Assessment, 11(4), 415.

Persons, J.B. (2008). The Case Formulation Approach to Cognitive-Behavior Therapy. Guildford Press, London.

Proudfoot, J., & Nicholas, J. (2010). Monitoring and evaluation in low intensity CBT interventions. Oxford guide to low intensity CBT interventions, 97-104.