Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia nervosa is a serious eating disorder characterized by an intense fear of weight gain, persistent behaviors that prevent weight gain, and a distorted perception of body weight and shape. Individuals with anorexia nervosa often restrict food intake to dangerous levels, sometimes accompanied by excessive exercise or purging behaviors. This disorder has profound physical and psychological effects, including severe weight loss, nutrient deficiencies, and emotional distress. Without appropriate treatment, anorexia nervosa can lead to long-term health complications and even be life-threatening. Evidence-based approaches, such as cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED) and specialist supportive clinical management (SSCM), are effective in addressing factors that maintain the disorder.

Showing 1 to 23 of 23 results

Insufficient Self-Control

Insufficient Self-Control

Recognizing Anorexia Nervosa

Recognizing Anorexia Nervosa

Overcoming Eating Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Overcoming Eating Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Overcoming Your Eating Disorder: Workbook

Overcoming Your Eating Disorder: Workbook

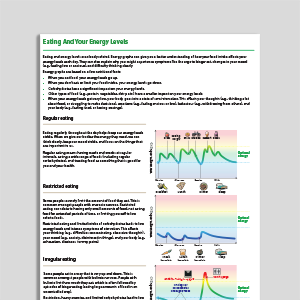

Eating And Your Energy Levels

Eating And Your Energy Levels

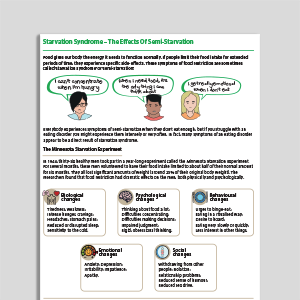

Starvation Syndrome – The Effects Of Semi-Starvation

Starvation Syndrome – The Effects Of Semi-Starvation

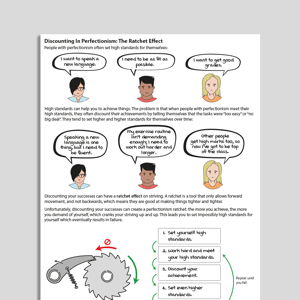

Discounting In Perfectionism – The Ratchet Effect

Discounting In Perfectionism – The Ratchet Effect

Demanding Standards – Living Well With Your Personal Rules

Demanding Standards – Living Well With Your Personal Rules

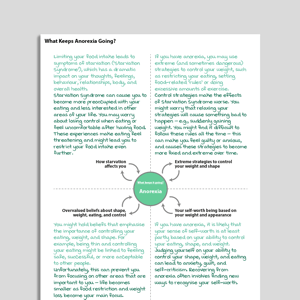

What Keeps Anorexia Going?

What Keeps Anorexia Going?

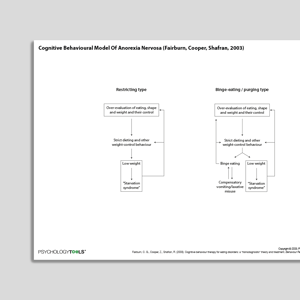

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Anorexia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Anorexia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Assessment

-

Eating Attitudes Test 26 (EAT-26)

| Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, Garfinkel | 1982

- Test (PDF)

- Test (Word)

- Scoring and interpretation

- Website link

- Reference Garner et al. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871-878

-

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE)

| Fairburn, Cooper, O’Connor | 2014

- Interview

- Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

- Questionnaire for Adolescents (EDE-A)

- Reference Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & O’Connor, M. (1993). The eating disorder examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 1-8.

Guides and workbooks

- Taming the hungry bear: Your way to recover from chaotic overeating | Kate Williams

Information (Professional)

- Topics to cover when assessing the eating problem | Fairburn | 2008

Self-Help Programmes

-

Break Free From ED (Workbook)

| Centre For Clinical Interventions | 2022

- Module 1: What Are Eating Disorders?

- Module 2: What Keeps Eating Disorders Going?

- Module 3: Understanding The Number On The Scale

- Module 4: Self-Monitoring

- Module 5: Food And Energy

- Module 6: Eating For Recovery - Part 1

- Module 6: Eating For Recovery - Part 2

- Module 8: Binge Eating

- Module 9: Purging

- Module 10: Driven Exercise

- Module 11: Body Image 1 - Body Checking

- Module 12: Body Image 2 - Body Avoidance

- Module 13: Core Beliefs

- Module 14: Maintaining Your Gains And Dealing With Setbacks

- Appendix: Getting Educated About Eating Disorders

Treatment Guide

- Eating Disorders: Recognition And Treatment (NICE Guideline) | NICE | 2020

- Cognitive Remediation Therapy For Anorexia Nervosa (Treatment Manual) | Tchanturia, Davies, Reeder, Sykes | 2010

- Group cognitive remediation therapy for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: The flexible thinking group | Maiden, Baker, Espie, Simic, Tchanturia | 2014

Video

- Eating disorders from the inside out | Dr Laura Hill | 2012

What Is Anorexia Nervosa?

Signs and Symptoms

The DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa include:

Persistent restriction of food intake leading to significantly low body weight.

Intense fear of gaining weight or persistent behavior interfering with weight gain, even at a low weight.

Disturbance in the way one’s body weight or shape is experienced, undue influence of body weight or shape on self-evaluation, or lack of recognition of the seriousness of low body weight.

The ICD-11 similarly emphasizes a deliberate effort to maintain low body weight, fear of weight gain, and a distorted body image. Unlike DSM-5, ICD-11 explicitly includes subtypes, such as the restrictive type (characterized by food restriction alone) and the binge-purge type.

Incidence and Risk Factors

Anorexia nervosa has an estimated lifetime prevalence of 1–2% in women and 0.1–0.2% in men, with the majority of cases developing during adolescence or early adulthood (Treasure et al., 2010; Smink et al., 2012). Risk factors for anorexia nervosa are multifaceted and include genetic, psychological, and environmental contributors. Genetic predisposition can play a role, with twin studies indicating a degree of heritability (Trace et al., 2013). Personality traits such as perfectionism and high levels of anxiety increase vulnerability (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005). Environmental factors, including societal and cultural pressures that idealize thinness, can contribute to the development of anorexia nervosa (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2016). Family environments where weight, appearance, or control are highly emphasized, as well as histories of trauma or abuse, are also associated with the onset of the disorder (Wonderlich et al., 2007).

Psychological Models and Theories of Anorexia Nervosa

Cognitive Behavioral Models

Fairburn and colleague’s (1999) original cognitive behavioral model proposed that the central feature of anorexia nervosa is an extreme need to control eating, which is associated with other ‘characteristic’ features of the disorder, such as perfectionism and perceived ineffectiveness. Once attempts to restrict eating begin, they are reinforced by several mechanisms, including starvation effects and “the fact that control over eating directly enhances the person's sense of being in control and thereby their self-worth” (Fairburn et al., 1999, p.4). Fairburn and colleague’s (2003) more recent transdiagnostic cognitive behavioral model emphasizes the role of dysfunctional beliefs about eating, shape, weight, and their control in maintaining anorexia nervosa (and other eating disorders, such as bulimia nervosa). According to this model, these beliefs lead to maladaptive control strategies (e.g., food restriction and other weight control behaviors), resulting in cycles of reinforcement that sustain the disorder. Other factors emphasised in this model include low self-esteem, perfectionism, and mood intolerance.

Family Systems Models

Early theories informing family therapy for individuals with anorexia nervosa assumed that specific types of family organization or pattern of family interaction contributed to the development and maintenance of problems in the family system, including eating disorders (e.g., Minuchin et al., 1978; Selvini-Palazzoli, 1974). Since then, newer family-focused models and treatments have evolved, such as family-based treatment for anorexia nervosa (FBT; Lock & Grange, 2015) and anorexia focused family therapy (FT-AN; Eisler et al., 2016). These approaches view families as an important resource that can support individuals in their recovery from anorexia nervosa.

Cognitive Interpersonal Model

The cognitive-interpersonal model (Schmidt & Treasure, 2006; Treasure et al., 2020) emphasizes the interplay between cognitive traits and interpersonal dynamics in the development and maintenance of anorexia nervosa. According to this model, predisposing traits, such as obsessive-compulsive tendencies and anxious avoidance (particularly of close relationships), increase vulnerability to AN and contribute to its maintenance by fostering pro-anorexia beliefs and behaviours. Key maintaining factors in this model include perfectionism, cognitive rigidity, experiential avoidance, pro-anorexia beliefs, and starvation-related processes. This model diverges from cognitive-behavioral models of anorexia nervosa in several ways, including placing less emphasis on the role of weight and shape concerns.

Psychodynamic Models

Psychodynamic models of anorexia nervosa highlight the emotional and relational difficulties that underlie the disorder. These approaches suggest that eating disorder symptoms often stem from feelings of ineffectiveness, loss of control, challenges in managing and understanding emotions, a disrupted sense of self, and relational difficulties (Friederich et al., 2023). Within this framework, disordered eating and focus on the body are seen as defenses and coping strategies for managing these deeper struggles. Modern psychodynamic therapies incorporate this understanding while actively addressing symptoms like restrictive eating and weight loss (Zipfel et al., 2014).

Evidence-Based Psychological Approaches for Anorexia Nervosa

Eating disorder focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-ED), which encompasses approaches such as ‘enhanced’ CBT (CBT-E; Fairburn et al., 2015), is an effective treatment for anorexia nervosa. CBT-ED is designed specifically for eating disorders and targets distorted beliefs about shape, weight, and eating. It also incorporates strategies for addressing perfectionism, low self-esteem, interpersonal difficulties, and emotional regulation. Research indicates that CBT-ED can help improve eating disorder symptoms, broader psychopathology, and physical health outcomes (i.e., body mass index) (e.g., Galsworthy-Francis & Allan, 2014).

Family therapies for anorexia nervosa such as eating disorder focused family therapy (FT-AN) is particularly effective for adolescents with anorexia nervosa (Austin et al., 2024). FT-AN involves families taking an active role in helping the patient restore weight and reduce eating disorder behaviors while gradually returning control to the individual. Other key elements FT-AN and associated approaches such as family based treatment (FBT; Lock & Grange, 2015) include formulation, externalising the eating disorder, and individual sessions with the young person.

The Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA; Schmidt et al., 2014) is an effective cognitive-interpersonal therapy (García & Marcos, 2024) that is centred around a patient manual (Schmidt et al., 2019). It targets four key maintenance factors: rigid, perfectionistic thinking styles; socio-emotional difficulties, such as emotion recognition and avoidance; positive beliefs about anorexia; and unhelpful responses from close others, like criticism. Treatment includes core modules (e.g., formulation) and optional ones (e.g., building a non-anorexic identity).

Specialist Supportive Clinical Management (SSCM; McIntosh et al., 2006) is an evidence-based treatment for anorexia nervosa that combines clinical management with supportive psychotherapy (McIntosh et al., 2005). The approach emphasizes safety, education, and support, alongside acceptance, collaboration, and a focus on client strengths. SSCM centers on normalizing eating, weight restoration, and addressing dietary patterns. Therapy is structured into three phases: orientation and goal setting, monitoring progress and supporting eating and weight goals, and concluding therapy with future planning.

Focal psychodynamic therapy (FPT; Friederich et al., 2019) is an evidence-based, psychodynamic approach for the outpatient treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa (Zipfel et al., 2014). It emphasizes understanding the emotional and relational underpinnings of anorexia nervosa and is divided into three phases: building a therapeutic alliance, addressing pro-anorectic behaviors, and exploring self-esteem; examining relationships and their link to eating behaviors; and integrating positive changes into everyday life.

Resources for Working with Anorexia Nervosa

Psychology Tools offers resources for understanding and treating anorexia nervosa, including:

Cognitive-behavioral formulations and worksheets for addressing maladaptive thoughts and behaviors.

Handouts explaining the maintenance of anorexia nervosa.

Exercises for emotion regulation and distress tolerance.

Psychoeducational materials for families supporting individuals with anorexia.

References and Further Reading

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA.

Cassin, S. E., & von Ranson, K. M. (2005). Personality and eating disorders: A decade in review. Clinical Psychology Review, 25, 895–916.

Eisler, I., Simic, M., Blessitt, E., & Dodge, L. (2016). Maudsley service manual for child and adolescent eating disorders (revised). Child and Adolescent Eating Disorders Service, South London and the Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust.

Fairburn, C. G., Bailey-Straebler, S., Basden, S., Doll, H. A., Jones, R., Murphy, R., ... & Cooper, Z. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 64-71.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41, 509–528.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2009). Enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT-E): An update. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22, 556–562.

Fisher, C. A., Skocic, S., Rutherford, K. A., & Hetrick, S. E. (2019). Family therapy approaches for anorexia nervosa. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Issue 5. Art. No.: CD004780.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Ciao, A. C., & Accurso, E. C. (2016). Sociocultural influences on eating disorders. In L. Smolak & M. P. Levine (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of eating disorders (pp. 157–171). Wiley.

Friederich, H. C., Zipfel, S., & Wild, B. (2023). Psychodynamic therapies and eating disorders. In P. Robinson, T. Wade, B. Herpertz-Dahlmann, F. Fernandez-Aranda, J. Treasure, & S. Wonderlich (Eds.), Eating disorders: An international comprehensive view (pp. 1-20). Springer.

Fernández García, S., & Quiles Marcos, Y. (2024). Effectiveness of the Maudsley Model of Anorexia Nervosa Treatment for Adults: A systematic review. European Eating Disorders Review, 32, 1227-1241.

Galsworthy-Francis, L., & Allan, S. (2014). Cognitive behavioural therapy for anorexia nervosa: a systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 34, 54-72.

Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2010). Family-based treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(4), 279–291.

Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2015). Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. Guilford Press.

Minuchin, S., Baker, L., Rosman, B. L., Liebman, R., Milman, L., & Todd, T. C. (1975). A conceptual model of psychosomatic illness in children: Family organization and family therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 1031–1038.

Schmidt, U., & Treasure, J. (2006). Anorexia nervosa: Valued and visible. A cognitive‐interpersonal maintenance model and its implications for research and practice. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 45, 343-366.

Schmidt, U.. Startup, H., & Treasure, J. (2019). A cognitive interpersonal therapy workbook for treating anorexia nervosa: The Maudsley model. Routledge.

Schmidt, U., Wade, T. D., & Treasure, J. (2014). The Maudsley model of anorexia nervosa treatment for adults (MANTRA): Development, key features, and preliminary evidence. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 28, 48–71.

Selvini-Palazzoli M. (1974). Self starvation: From the intrapsychic to the transpersonal approach to anorexia nervosa. Chaucer.

Smink, F. R., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25(6), 543–548.

Trace, S. E., Baker, J. H., Peñas-Lledó, E., & Bulik, C. M. (2013). The genetics of eating disorders. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 589–620.

Treasure, J., Willmott, D., Ambwani, S., Cardi, V., Clark Bryan, D., Rowlands, K., & Schmidt, U. (2020). Cognitive interpersonal model for anorexia nervosa revisited: The perpetuating factors that contribute to the development of the severe and enduring illness. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9, 630 – 644.

Treasure, J., Claudino, A. M., & Zucker, N. (2010). Eating disorders. The Lancet, 375(9714), 583–593.

Wonderlich, S. A., Crosby, R. D., Mitchell, J. E., et al. (2007). Personality subtypes in eating disorders: Validation of a classification approach. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 116(2), 295–303.

World Health Organization. (2022). International Classification of Diseases, 11th Revision (ICD-11). WHO.

Zipfel, S., Wild, B., Groß, G., Friederich, H. C., Teufel, M., Schellberg, D., ... & Herzog, W. (2014). Focal psychodynamic therapy, cognitive behaviour therapy, and optimised treatment as usual in outpatients with anorexia nervosa (ANTOP study): randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 383, 127-137.