Bulimia Nervosa

Bulimia nervosa is a serious eating disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating alongside compensatory behaviors to prevent weight gain, such as self-induced vomiting, excessive exercise, or misuse of laxatives. Unlike anorexia nervosa, individuals with bulimia nervosa often maintain a normal or above-normal weight, making the condition less visible but no less severe. This disorder affects emotional, physical, and social well-being, and can result in life-threatening health complications if untreated. Evidence-based treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT-ED) have shown significant efficacy in reducing symptoms of bulimia nervosa.

Showing 1 to 20 of 20 results

Insufficient Self-Control

Insufficient Self-Control

Recognizing Bulimia Nervosa

Recognizing Bulimia Nervosa

Overcoming Eating Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Overcoming Eating Disorders (Second Edition): Therapist Guide

Overcoming Your Eating Disorder: Workbook

Overcoming Your Eating Disorder: Workbook

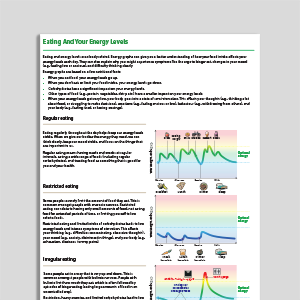

Eating And Your Energy Levels

Eating And Your Energy Levels

What Keeps Bulimia Going?

What Keeps Bulimia Going?

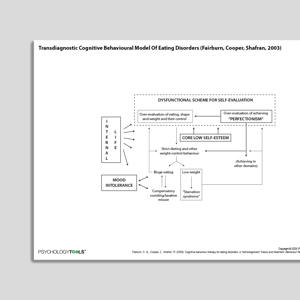

Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Eating Disorders (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Transdiagnostic Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Eating Disorders (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

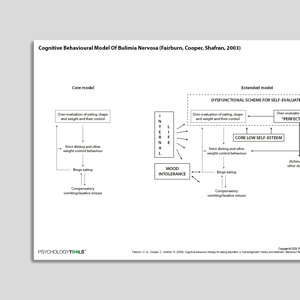

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Bulimia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Cognitive Behavioral Model Of Bulimia Nervosa (Fairburn, Cooper, Shafran, 2003)

Links to external resources

Psychology Tools makes every effort to check external links and review their content. However, we are not responsible for the quality or content of external links and cannot guarantee that these links will work all of the time.

Assessment

-

Eating Attitudes Test 26 (EAT-26)

| Garner, Olmsted, Bohr, Garfinkel | 1982

- Test (PDF)

- Test (Word)

- Scoring and interpretation

- Website link

- Reference Garner et al. (1982). The Eating Attitudes Test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871-878

-

Eating Disorder Examination (EDE)

| Fairburn, Cooper, O’Connor | 2014

- Interview

- Questionnaire (EDE-Q)

- Questionnaire for Adolescents (EDE-A)

- Reference Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & O’Connor, M. (1993). The eating disorder examination. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 1-8.

Guides and workbooks

- Taming the hungry bear: Your way to recover from chaotic overeating | Kate Williams

Information (Professional)

- Topics to cover when assessing the eating problem | Fairburn | 2008

Self-Help Programmes

-

Break Free From ED (Workbook)

| Centre For Clinical Interventions | 2022

- Module 1: What Are Eating Disorders?

- Module 2: What Keeps Eating Disorders Going?

- Module 3: Understanding The Number On The Scale

- Module 4: Self-Monitoring

- Module 5: Food And Energy

- Module 6: Eating For Recovery - Part 1

- Module 6: Eating For Recovery - Part 2

- Module 8: Binge Eating

- Module 9: Purging

- Module 10: Driven Exercise

- Module 11: Body Image 1 - Body Checking

- Module 12: Body Image 2 - Body Avoidance

- Module 13: Core Beliefs

- Module 14: Maintaining Your Gains And Dealing With Setbacks

- Appendix: Getting Educated About Eating Disorders

Treatment Guide

- Eating Disorders: Recognition And Treatment (NICE Guideline) | NICE | 2020

Video

- Eating disorders from the inside out | Dr Laura Hill | 2012

What Is Bulimia Nervosa?

Bulimia nervosa is marked by a cycle of binge eating and compensatory behaviors to counteract the effects of binge episodes. According to DSM-5, diagnostic criteria include:

Recurrent episodes of binge eating, characterized by eating an objectively large amount of food in a short time and feeling a lack of control during the episode.

Engagement in compensatory behaviors such as vomiting, fasting, or excessive exercise to prevent weight gain.

Binge and compensatory behaviors occurring at least once a week for three months.

Self-esteem unduly influenced by body shape and weight.

The ICD-11 similarly emphasizes the cyclical nature of binge eating and purging behaviors, alongside significant distress and functional impairment. Unlike anorexia nervosa, individuals with bulimia nervosa typically have a body weight within the normal range.

Incidence and Risk Factors

Bulimia nervosa affects 1–3% of women and approximately 0.1–0.5% of men in their lifetime, with the highest prevalence in adolescents and young adults (Smink et al., 2012). Risk factors include:

Genetic predisposition: Family studies suggest a heritable component to bulimia nervosa.

Personality traits: Impulsivity, perfectionism, and difficulty managing emotions may increase vulnerability (Cassin & von Ranson, 2005).

Sociocultural influences: Societal pressure to achieve an ideal body shape and exposure to media promoting thinness significantly contribute to the development of bulimia (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2016).

Early experiences: A history of trauma, abuse, or parental criticism about weight can increase susceptibility.

Psychological Models and Theories Of Bulimia Nervosa

Early cognitive behavioral models suggest that bulimia nervosa is characterized by a tendency to base self-worth on weight and body shape (Fairburn, 1981), leading to extreme dieting. When individuals inevitably break their strict dietary rules, they often engage in all-or-nothing thinking (e.g., “I’ve failed, so I might as well eat everything”). Dichotomous thinking, combined with the effects of dietary restriction, results in episodes of binge eating that feel out of control. As binge eating tends to increase concerns about weight and body shape, individuals frequently resort to compensatory behaviors, such as self-induced vomiting, which further reinforces binge eating (Shafran & de Silva, 2003).

Fairburn and colleagues' more recent ‘transdiagnostic’ cognitive-behavioral model (2003) also emphasizes the role of dysfunctional beliefs about eating, weight, and control in bulimia nervosa. However, this model identifies additional maintaining factors such as low self-esteem, perfectionism, interpersonal difficulties, and difficulty tolerating negative emotions.

Other cognitive models have focused on specific thinking patterns related to binge eating, such as ‘permissive thoughts’ (Cooper et al., 2004). It has also been proposed that binge eating may serve as a way for some individuals to escape distressing thoughts and emotions (Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991).

Sociocultural models take a broader perspective by emphasizing the influence of cultural ideals of thinness, which create pressure to achieve unrealistic body standards (Stice, 1994). This external pressure interacts with internal vulnerabilities, such as low self-esteem, to perpetuate the cycle of binge eating and purging.

Evidence-Based Psychological Approaches for Bulimia Nervosa

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Eating disorder focused cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT-ED), which encompasses approaches such as ‘enhanced’ CBT (CBT-E; Fairburn et al., 2015), has the strongest evidence base for treating bulimia nervosa (Slade et al., 2018). CBT-ED focuses on challenging maladaptive beliefs about weight, shape, and eating, while addressing disordered eating behaviors such as binge eating and purging. Research has consistently demonstrated significant reductions in symptom frequency and improved quality of life following CBT-ED (e.g., Fairburn et al., 2009).

Family-Based Therapy (FBT)

FBT is effective for adolescents with bulimia nervosa (Monteleone et al., 2022). This approach empowers families to support recovery by creating a structured eating environment and addressing behaviors associated with the disorder (Lock & Le Grange, 2015).

Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)

DBT targets emotion dysregulation, which is often a core feature of bulimia nervosa, by teaching skills such as distress tolerance, emotional regulation, and interpersonal effectiveness (Linehan & Chen, 2005). Research suggests that DBT might help reduce binge-purge behaviors and improve emotional well-being (Safer et al., 2009).

Resources for Working with Bulimia Nervosa

Psychology Tools offers a comprehensive range of resources for supporting individuals with bulimia nervosa, including:

Cognitive behavioral formulations and worksheets.

Psychoeducational handouts about the cycle of binge eating and purging.

Mindfulness and self-compassion exercises.

Guides for parents and caregivers to support recovery.

References and Further Reading

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). APA.

Cooper, M. J., Wells, A., & Todd, G. (2004). A cognitive model of bulimia nervosa. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 43, 1-16.

Fairburn, C. G.(1981). A cognitive-behavioral approach to the management of bulimia. Psychological Medicine, 11, 697-706.

Fairburn, C. G., Bailey-Straebler, S., Basden, S., Doll, H. A., Jones, R., Murphy, R., ... & Cooper, Z. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 64-71.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2003). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders: A “transdiagnostic” theory and treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(5), 509–528.

Fairburn, C. G., Cooper, Z., & Shafran, R. (2009). Enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for eating disorders (CBT-E): An update. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 22(6), 556–562.

Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Ciao, A. C., & Accurso, E. C. (2016). Sociocultural influences on eating disorders. In L. Smolak & M. P. Levine (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of eating disorders (pp. 157–171). Wiley.

Heatherton, T. F., & Baumeister, R. F. (1991). Binge eating as escape from self-awareness. Psychological Bulletin, 110, 86-108.

Linehan, M. M., & Chen, E. Y. (2005). Dialectical behavior therapy for eating disorders. In A. Freeman, S.H. Felgoise, C.M. Nezu, A.M. Nezu & M.A. Reinecke (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cognitive behavior therapy (pp. 168–171). Springer.

Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2015). Treatment manual for anorexia nervosa: A family-based approach. Guilford Press.

Monteleone, A. M., Pellegrino, F., Croatto, G., Carfagno, M., Hilbert, A., Treasure, J., ... & Solmi, M. (2022). Treatment of eating disorders: a systematic meta-review of meta-analyses and network meta-analyses. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 142, 104857.

Safer, D. L., Telch, C. F., & Chen, E. Y. (2009). Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. Guilford Press.

Shafran, R., & P. de Silva (2003). Cognitive-behavioral models. In Treasure, J., Schmidt, U., & Van Furth, E. (Eds.), The handbook of eating disorders (2nd ed). (pp.121-138).

Slade, E., Keeney, E., Mavranezouli, I., Dias, S., Fou, L., Stockton, S., ... & Kendall, T. (2018). Treatments for bulimia nervosa: A network meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 48, 2629-2636.

Smink, F. R., van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology, course, and outcome of eating disorders. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25(6), 543–548.

Stice, E. (1994). Review of the evidence for a sociocultural model of bulimia nervosa and an exploration of the mechanisms of action. Clinical Psychology Review, 14, 633-661.